Were Iris Barry’s life to be proposed as a fictional subject, it might be laughed out of court as hopelessly implausible. Born in an outer suburb of Birmingham to a brass founder and a professional palm-reader who practised under the name of Madame Pandora, she died in Provence as an antique dealer and lover of an olive-oil smuggler some 20 years her junior. In between she wrote poetry and biography, got to know Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Edith Sitwell and W. B. Yeats, bore two children to Wyndham Lewis and became the first film reviewer to write for a serious British journal. Moving to the US, she consorted with Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, Virgil Thomson and Luis Buñuel, founded and curated America’s first-ever film archive at the Museum of Modern Art, worked during the Second World War with the likes of Orson Welles, Frank Capra and John Huston to develop propaganda movies, was awarded the Légion d’honneur, narrowly escaped kidnapping by Corsican bandits and nearly lost her naturalised US citizenship when targeted by anti-Communist witch-hunters. In her own words, “It has all been very interesting”.

Given such a protagonist it would be hard to produce a dull book, and Robert Sitton’s biography makes for lively reading – much helped by lavish quotation from Barry’s own spirited, if occasionally wayward, prose. Her early film criticism, for The Spectator and briefly for the Daily Mail, still reads well. In the teeth of widespread scorn – not least from the film industry– she insisted that films were more than an ephemeral, vulgar amusement, and that cinema represented a new art form worthy of as much serious critical attention as the novel or the theatre. Years before Cahiers du cinéma and Andrew Sarris, she formulated the essence of the auteurist theory, stating that “Every good film must have the impress of one mind, and one mind only, upon it” – that mind, in most cases, being the director’s.

Barry’s pioneering work as curator of films at MoMA followed naturally from her critical stance: if films were a significant art form, they must be preserved no less than books and paintings. But in Sitton’s chapters dealing with this crucial phase of her career, Barry herself often gets sidelined in favour of the museum’s Byzantine internal politics; like many high-minded cultural institutions, it seems to have been a hotbed of scheming, backstabbing and rampant ambition. Still, her personal life provides plenty of colour. Besides her liaison with the rebarbative Lewis she married twice, seemingly without much passion on either occasion, farmed out her children from infancy and pursued flings with (according to an old friend) “taxi drivers or kids in the street” before ending up with her Breton smuggler. In his concluding chapter Sitton notes, “I never met Iris Barry. Perhaps we might not have liked one another if I had.”

One person who did like her was the film-maker, screenwriter and fellow-founder (in 1925) of the London Film Society, Ivor Montagu. In his Sight and Sound obituary of Barry he recalled her “gaiety, wit, conquering charm…catholicism of taste and encyclopedic knowledge”, and hailed her as the “inspirer and patron saint of [film archives] in all lands”. For this last alone she deserves to be remembered.

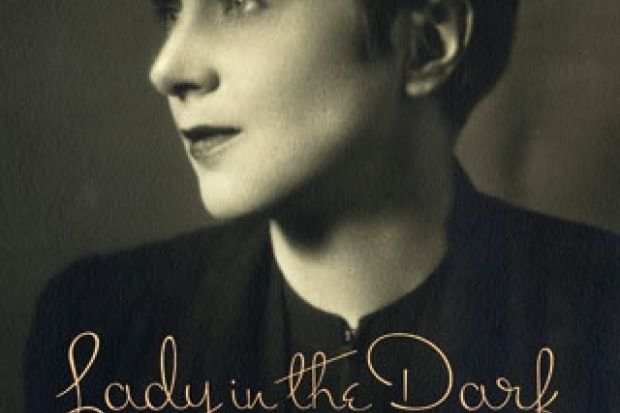

Lady in the Dark: Iris Barry and the Art of Film

By Robert Sitton

Columbia University Press, 496pp, £.50

ISBN 9780231165785

Published 1 April 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?