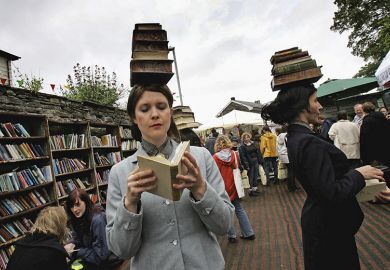

Source: Alamy

Got it covered: in its push towards open access, University College London is using its repository as a publishing platform to disseminate research

University budgets are under pressure. Libraries can no longer afford to subscribe to every journal – never mind every monograph – that academics might want to read. And hopes that open access might significantly ease the pressure are fading (in the UK, at least) as the government holds fast to its view that a managed transition to the fee-paying “gold” variety is the way forward.

What is a librarian to do?

For some observers, the answer is obvious: universities should do their own publishing. Many, of course, already have their own presses, but these are usually run on commercial lines.

In the UK at least, such presses typically have not embraced open access, yet the vast majority of universities have open repositories aimed at showcasing their own previously published research. So why don’t they take the apparently small extra step and use the repositories as publishing platforms in their own right?

This is what University College London plans to do.

The UCL Press imprint, which it had previously licensed to commercial publishers, was repatriated by the university earlier this year. UCL Press is now a department within the institution’s Library Services, whose director and acting group manager, Paul Ayris, told Times Higher Education that the germ of the idea had simply been his observation that, unlike UCL, “competitor” institutions already had their own presses, which “seemed a bit odd”.

But the wisdom of adopting “a more proactive approach to research dissemination” quickly became apparent to him.

One advantage is enabling postgraduates to publish earlier in their careers than would typically be possible, with student societies able to establish “overlay journals” on UCL’s repository. One example, known as Slovo – produced by postgraduates in Slavonic and East European studies – is already up and running, having been converted from its previous paper format after UCL Press’ “soft launch” in August.

Overlay journals are not a new concept. Most recently, a project known as Episciences began establishing mathematics epijournals on the arXiv open-access server. But Dr Ayris is unaware of any other university that hosts them on its own repository.

Dr Ayris also hopes that senior academics can be tempted to set up “fully fledged peer-reviewed journals” via the press, open to authors from around the world. And he has already uncovered significant interest among the UCL faculties, initially in the arts and social sciences, whom he has spoken to about their “publishing needs”.

He would also be open to requests to move journals previously published commercially on to UCL Press – provided they have at least one UCL academic on their editorial boards. Indeed, the press has already inherited one established organ: the Journal of Bentham Studies, which was previously published by UCL Library.

Publishing will be free to UCL staff with no external source of open-access fees. And while external academics will be charged, Dr Ayris’ financial aspiration is merely that the press be able to cover its own costs. For this reason, he hopes its fees – which have yet to be set – can be kept closer to the lower levels typically charged by pure gold open-access publishers such as PLoS and BioMed Central.

Ministering to the monograph

The other major inspiration for UCL Press was the need to address the “broken” monograph business model, as well as the reluctance of some arts, humanities and social science scholars to get involved with open access, Dr Ayris explained.

“Most commercially produced monographs are aimed at the library market because of their [high] price. But library budgets are so squeezed by meeting the demands of journal inflation that there is less and less money for monographs,” he said.

Hence, UCL Press will follow Manchester University Press in also publishing open-access monographs.

Dr Ayris sees open access as a potential saviour of the monograph, provided funders are willing to follow the example of the Wellcome Trust and cover publication charges. UCL academics – at least one of whom will have to sit on the editorial board managing the monograph series – again will be exempt from author charges.

The government-commissioned Finch report on open access regarded the monograph as too tough a nut to crack. The absence of publishing outlets and established funding streams also means there will be no requirement for monographs submitted to the 2020 research excellence framework to be open access (unlike papers). However, the funding councils have indicated that this is likely to change for subsequent exercises and the Higher Education Funding Council for England announced this month that it would provide £50,000 to support universities that participate in the forthcoming pilot of the Knowledge Unlatched project, which seeks to fund open-access monographs via pledges from library consortia.

Dr Ayris insisted that UCL was not trying to put commercial publishers out of business: they were “perfectly free” to replicate the open access business models being developed by UCL Press, as well as others such as the academic-led Open Book Publishers, the Open Library of the Humanities and Ubiquity Press (also based at UCL and advised by Dr Ayris). Nor are commercial publishers resting entirely on their laurels: both Springer and Palgrave Macmillan have announced open-access monograph options over the past 18 months.

Dr Ayris said that by sharing infrastructure and services, university presses can reduce costs and drive innovation more quickly.

With that in mind, UCL is leading a collaboration of 19 Western European universities – formally under way this month – which has established 35 prospective open-access monograph series in the arts and humanities. This could potentially lead to 180 individual titles.

Dr Ayris also hopes to conduct experiments in peer review and publication form. He suggested that the six-year REF cycle might make shorter-form monographs of about 100 pages (which he “hoped” UCL had thought of before Palgrave, which began offering them early this year) more popular than longer ones that take “20 years” to write.

He admitted it would not be easy to overcome the academic “custom and practice” that had preserved the traditional publishing model for so long. But he hoped that UCL Press’ high-end production values and association with the university’s prestige would help it fulfil its “boundless aspiration” to attract in time the “best” authors from across the world.

“Universities have a real chance to reassert their role in the research workflow by taking on…publishing and dissemination. Now is the time to do it,” he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?