The security alarm going off in the University of Cape Town’s School of Design – triggered by protesting students disrupting classes – is deafening. But a passing security guard smiles and gives a hand signal which seems to imply that this is just another day at a university that has been routinely racked by protests for several years.

A similar response from locals had been in evidence the previous day, when an international conference held at the university had been forced to pause by intermittent power blackouts. A shrug of the shoulders and embarrassed smiles seemed to say, “This should not be normal, but it is.”

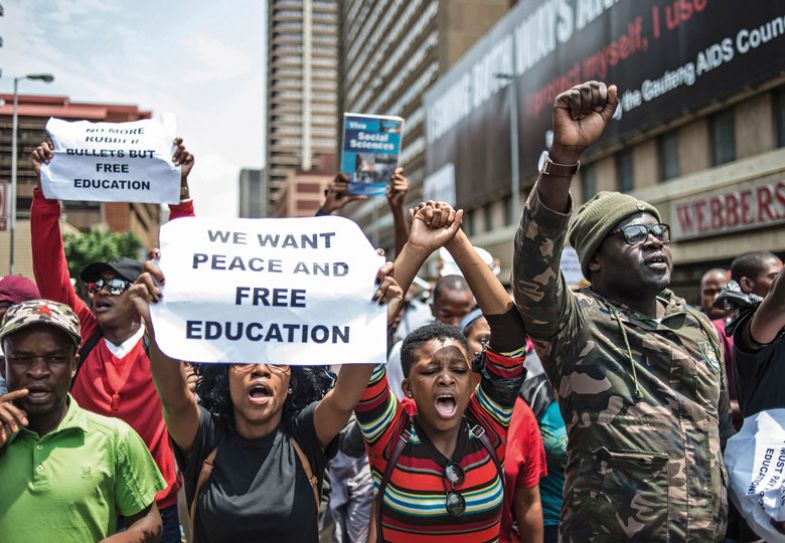

When Mamokgethi Phakeng became vice-chancellor of UCT in July 2018, there were high hopes that she could lead Cape Town and South African higher education forward after a disrupted few years. The Rhodes Must Fall protests that convulsed UCT’s campus in 2015 had ended when the hated statue of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes had been removed from the campus. And the Fees Must Fall revolt against tuition fee rises, which began at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand later the same year but soon spread to Cape Town – culminating in the firebombing of the office of Phakeng’s predecessor, Max Price – had resulted in outgoing president Jacob Zuma’s promise to abolish tuition fees for poorer students.

Phakeng, UCT’s second black female vice-chancellor and third black leader, was seen as a symbol of the country’s post-apartheid transformation. “There was enormous pressure and anger for a black person, ideally a black African woman, [to be appointed], and she was the right person at the right time,” according to Jonathan Jansen, who himself became the first black vice-chancellor of the formerly whites-only University of the Free State in 2009.

Phakeng, who was previously vice-principal of research and innovation at Pretoria’s University of South Africa, told Times Higher Education at the time of her appointment that her poor background would allow her to connect with the whole university population, “from the cleaners to the students to academics to management”. However, she also confided that emails were already circulating calling for her qualifications to be investigated. And after a bruising first four-year term, marked by a long-running governance investigation, staff unrest over bullying allegations and pay, and student demonstrations, she began a five-month sabbatical last October “to heal, reflect, rejuvenate, to read and to look back at my first term and say: ‘What has worked, what hasn’t, what am I going to do differently?’”

She did not get the chance to put her conclusions into practice, however. In February, shortly into her second term, she took early retirement in return for a large reported payoff.

Amanda Gouws, distinguished professor of political science at Stellenbosch University, says UCT’s problems started with Fees Must Fall, when many people accused Price of being too lenient with students who had protested violently. But “when he was replaced, there were already people saying Professor Phakeng is a problematic personality. The university wasn’t unified on her appointment and that very quickly influenced governance [for the worse],” she says.

“It was just a bad appointment, period, but conscious of the times,” reflects Jansen, who is now a distinguished professor in education at UCT’s neighbour, Stellenbosch, having stepped down from the University of the Free State in 2016. He says that in Phakeng’s wake, the UCT campus is even more racially divided, and student unrest has become endemic, with protests at the start of every university year over the non-registration of learners with outstanding fees.

As a result of the turbulence, many UCT donors have threatened to withdraw their funds, and some have followed through, Jansen adds. And the university’s reputation with the general public has suffered, too. “That damage to an institution takes a long time to recover from. It’s not that they lost a lot of money. It’s the real damage to the institution on the inside and the perception on the outside,” Jansen says.

While some of the turbulence at UCT relates to its own history and current situation, many observers see the problems at Africa’s top-ranked institution as a sign of deeper dysfunction across the sector.

Part of the problem is beyond universities’ control. When Zuma announced the scrapping of fees for lower-income students, having previously abandoned plans for fee rises, he was answered with widespread scepticism about how the pledge could be funded, and Zuma left office before he had to answer that question.

“That was his parting gift,” says Gouws. But the promise was “unfeasible” because of the dire finances of the country, meaning the money that Zuma’s successor, Cyril Ramaphosa, poured into the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) had to come from elsewhere – including research budgets.

“An immediate effect was the drop in the number of research scholarships funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) – no longer possible because all the money was taken away from postgraduate education and channelled to NSFAS,” she says.

Moreover, although the poorest students now have their fees waived (previously, they had to take on income-contingent loans), the system’s creators left out the “missing medium” – the children of mostly blue-collar workers whose income is just above the qualification threshold, according to Tawana Kupe, vice-chancellor of the University of Pretoria.

Kupe wants to see a sustainable, long-term funding model put forward. In the meantime, he urges the NSFAS to make decisions on who is entitled to funding more quickly because delays are “invariably the cause of protests” at the beginning of every academic year.

“A culture of persistent protest, leading to disruption of the teaching and learning programme, causes dysfunction in the long term and distrust by the public over the quality of education,” he says. This is causing low morale among academics and even leading some to quit because they cannot bear the constant upheaval, he adds.

Such a culture can be prevented by robust leadership, a good university council and good management, Kupe insists. But he calls the funding of South African higher education a “cancer” that is at the heart of most other problems in the sector but that is hard for individual universities to do anything about.

Wim de Villiers, vice-chancellor of Stellenbosch, also sees funding as the biggest problem for the sector.

“The national student aid scheme is unsustainable, utterly unsustainable, and politically it’s a minefield,” he tells THE. But “how the government is going to walk back from that in a pre-election year…That’s a tough one.”

When he first became vice-chancellor of Stellenbosch in 2015, de Villiers thought the focus of his work would be on research, teaching and learning. Instead, the university has faced one huge challenge after another: not only Fees Must Fall and the rolling blackouts that have affected South Africa since 2007 but also a drought in the Western Cape, a spate of gender-based violence and protests, and then the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Every year brings something,” he adds. “You’ve got to keep your eye on the ball.”

He believes this is one reason why physicians make good vice-chancellors: they have to deal with a range of problems, with each one commanding their full attention. “What we’re good at, without realising it, is compartmentalisation – we’re good at fighting fires because you’ve got to focus on one fire, then another without losing sight of the overall game plan.”

De Villiers sees the government’s inability or unwillingness to address the funding issue as symptomatic of wider inaction regarding higher education as it deals with what he calls South Africa’s “four horsemen of the apocalypse”: poverty, inequality, unemployment and corruption.

As a result, he says, ministers have “left [universities] to our own devices. Increasingly, I believe government is an unreliable partner in terms of our funding, so we have to find different ways of doing that if we want to continue on this trajectory of being Africa’s foremost research-intensive university.” (Stellenbosch is in the 251-300 range in THE’s latest World University Rankings, alongside Wits. Cape Town is ranked in 160th place.)

Gouws agrees. She says universities can come up with plans and ideas to tackle the issues they face – another being those rolling power outages, which have obliged universities to buy expensive back-up generators – but nothing is implemented by government because it has no political will.

“We are not being governed,” she says. “Everything is dysfunctional. We have a minister for higher education who just is not concerned. To say ‘government should do this, that and the other’ is futile because government will not do this, that and the other.”

This level of neglect is prevalent across other levels of education, she warns, but problems in lower-level education come home to roost in higher education, forcing universities themselves to “deal with” them. Schools are in a state of “national crisis”, rife with sexual harassment and violence, delinquent teachers and failure to provide transport for students who need it. As a result, Gouws says, students come to university underprepared, taking up more resources and staff time and, even then, often failing to finish their degrees.

Yet while South African universities may not be able to do anything about dysfunction in wider society, they can certainly do more to address their own management and governance failings, according to Jansen. In his latest book, Corrupted: A study of chronic dysfunction in South African universities, Jansen sets out the extent of these failings. One example, he tells THE, is Pretoria’s Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, which was shut down by protests for months in 2021, yet thousands of students still received their degrees as if nothing had happened.

He says constant disruption is the most visible sign that a university is dysfunctional. And the cause is usually a lack of two things: institutional capacity – the ability to lead, manage and administer – and institutional integrity – the steering academic values that buffer universities against instability. He says that during Phakeng’s tenure, both were missing at UCT. He alleges that Phakeng was unable to lead a complex and divided institution and failed to follow basic governance procedure, leading her into conflict with most people she encountered, including him.

In his book, Jansen quotes an old African proverb: “When elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.” In this situation, he says, everyone has been hurt by the conflict: students’ education, staff’s motivation and alumni pride.

“UCT will land on its feet because of its history, but this kind of leadership ineptness has a corrosive effect on university systems of governance and administration,” he says. “The next time it happens, you’re not going to be as strong. God help us if they make another weak appointment. An institution stands and falls by its leadership – not just one person, but plural.”

Jansen’s book recounts 20 occasions when the government has had to intervene in defective university governance since 1994. And just last month, a government-appointed assessor of Phakeng’s previous institution, the University of South Africa (Unisa), advised the minister to place the open distance learning institution in administration and to relieve its management and council of their duties.

In his investigation, the assessor, University of Pretoria vice-principal Themba Mosia, found a “cauldron of instability characterised by a culture of fear, intimidation, bullying, maladministration, financial irregularities, poor student services, academic malpractices, leakage of confidential records and questionable management and council decisions”. For example, according to news reports, he highlighted spending of 3 million rand (£125,000) on renovations, new furniture and appliances for the official residence of vice-chancellor Puleng LenkaBula – who, nevertheless, has still not moved in since being appointed at the beginning on 2021.

“There is overwhelming evidence that the functioning and efficacy of both council and management fall below an expected standard of an effective university,” Mosia concluded.

Good governance is essential to a well-functioning university, says Kupe, Mosia’s Pretoria colleague. “The critical part is the university council and in the dysfunctional universities that’s where the problem has been.”

He says good governing councils contain people with the necessary expertise and experience, not only in higher education but also accounting, fundraising and finance, for example. But the members of poorly run councils either lack such expertise or prioritise their own interests over that of the institution.

“There are very basic ingredients to having a good council – people with integrity who understand conflicts of interest, people with experience, but, most importantly, people who understand that a good stable university is a benefit to society, not to themselves,” he says.

And as they are responsible for appointing the vice-chancellor, a council without the right members is likely to select the wrong person for the top job, he adds.

Jansen argues that dysfunction is both an enabler and a consequence of corruption because it makes people doubt the validity of institutional rules.

“When you weaken those rules of governance it enables the predators to come in and basically loot the place. We often think of dysfunction as the lack of resources or something else, but what if dysfunction is part of the plan? What if it is designed to weaken systems in order for the looting to take place?” he asks.

He does not believe that there is corruption at UCT, but he does see it elsewhere. The most famous recent example of this can be seen at the University of Fort Hare, where members of staff have been killed, threatened and kidnapped in the past year. It is believed that these incidents were the direct result of vice-chancellor Sakhela Buhlungu's attempts to stamp out fraud and corruption within the institution. Buhlungu previously told THE that the troubles at Fort Hare are evidence of the phenomenon of “university capture” by rogue elements intent on lining their own pockets through corrupt dealing.

Attacks on university staff have not been restricted to Fort Hare. Multiple academics have been shot dead in recent years, with suspicions that these killings were also linked with corruption. And Jansen has seen the “dark side” of universities many times during his career. Another example is a vice-chancellor who travelled to work in a gold-plated Jaguar with AK-47 rifles in its boot. Armed guards, Jansen adds, are commonplace.

He believes the problems go back to apartheid-era government neglect of historically black universities – disparaged at the time as “bush colleges”. Universities such as Fort Hare were “cut off at the knee over 100 years”, Jansen says. Hence, many of them entered the post-apartheid era, in 1994, in a state of dysfunction that they “simply didn’t have the leaders” to put right.

“You can turn around a private sector organisation quickly, but you can’t turn around a university which has lost all sense of itself,” Jansen adds. “One of the big mistakes we made was to think that higher education...was exempt from the kind of corruption that we saw in other public entities.” In reality, with the vast majority of its funding coming from the state, a university is liable to suffer the same fate as any municipal government or hospital in South Africa – with its resources “ready to be looted”. And when the majority of people begin to accept this looting as normal, it becomes very hard to turn things around, Jansen says.

It is not the case that every “historically disadvantaged” institution was dysfunctional. Another Cape Town institution, the University of the Western Cape, is now relatively successful, Jansen points out. Meanwhile, according to Gouws, Fort Hare itself was actually a very well-functioning institution pre-transition, having educated Nelson Mandela and other notable political leaders. She sees high staff turnover more recently as the point at which things started to go wrong. She says the current level of corruption at Fort Hare is “exceptional”, but the capture of public institutions for the sole purpose of self-enrichment is commonplace. This involves finding “ways to get round the public procurement act" so that all the money "goes into patronage networks”.

Such phenomena came as a shock to Jansen when he first became aware of them. Previously, he had held the “idealistic” view that universities were focused on advanced research, deep enquiry and scholarly debate. “I have a particular passion to make sure that the African university doesn’t stand back when it comes to the world of universities, so you can imagine the disappointment when you see people literally stealing the resources of a university, undermining it in order to steal more,” he says.

“A student from a poor community has one shot out of poverty and that’s education,” he adds. “Parents know that if it doesn’t work out, they’re basically condemned to a life of poverty.” But corruption and dysfunction are a guarantee that education won’t “work out” for the students who suffer from its debilitating effect on institutions, including a decline in public confidence.

“It is important for us in South Africa to get as many kids as possible into higher education,” he says, “but also, for those who get in, that the degree they get is worth the paper it is printed on.”

If degree certificates are indeed to retain their value, it is evident that an increase in both government funding and universities’ capacity to use it wisely is necessary. Failing that, while Rhodes and fees may have fallen, the barriers to a fairer and more prosperous South African will remain insurmountable.