Careers intelligence: distance mentoring early career researchers

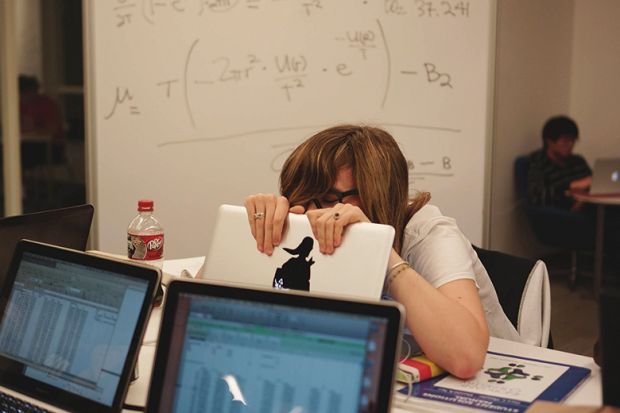

Source: Getty

Academic mentorship is expected to be personal, with tailored advice provided by a mentor who can draw on personal experience, usually via the medium of face-to-face conversation. While the coronavirus has largely done away with what is considered “usual” in academia, it does not mean that those starting their academic careers need any less guidance.

For Ellen Boeren, professor of adult education and deputy director of research at the University of Glasgow’s School of Education, mentoring is now especially important for those on fixed-term contracts and recent PhD graduates.

“They are likely feeling lost in what the future might bring. It will be important for them to express their feelings towards someone they can trust,” she said.

READ MORE: Careers intelligence: will the virus crisis change academic careers?

While mentors cannot change the academic labour market for them, there are still ways to help early career researchers, she said. The focus on publications in peer-reviewed, high-impact journals is unlikely to change any time soon, for example, so, during times like these, mentors and mentees could find a way to cooperate on writing projects.

“In our school we ran a big writing retreat last week where colleagues – including some early career researchers – could block off some time to prepare research proposals,” she said. “Three times a day, we checked in on Zoom for a group chat on how everyone was progressing. It was a good combination of peer support combined with funding insights offered by professors running the research directorate in the school.”

For Michele Veldsman, a postdoctoral research scientist at the University of Oxford, the main thing to remember is that mentorship must be personalised, whether online or in person. “Some people will be looking for personal and career advice; others want more practical help and want you to proof their CV or advise them how to get funding,” she said.

Dr Veldsman said that it was important for mentors to check in regularly but also to gauge how often people want to be contacted. “Do it too often and it can feel as if a supervisor is checking up on them, so at the start make sure they are honest about what suits them,” she advised, adding that setting an agenda before a meeting is useful, so the mentee can be sure they get what they need during the allotted time.

Dr Veldsman is part of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping International Mentoring Programme, an initiative involving 500 scientists every year. The mentorship takes place wholly online as scientists take part from across the world. “It’s been very successful. A lot depends on the relationship you set up and keeping in touch regularly,” she said.

Although some people will find the idea of distance mentorship difficult, there are benefits to it, Dr Veldsman said. For example, one academic she was mentoring had a long list of questions, but they were only able to get through half of them in the chat. Later that day, however, Dr Veldsman had spare time, so she created a shared Google doc and filled in the answers they hadn’t got to.

“It can be easier to find the time for mentoring sessions when you don’t have the pressure of finding a time to meet face to face, which can depend on whether you are on campus,” she said.

Beth Tigges, an associate professor at the University of New Mexico College of Nursing, advised using several forms of communication but prioritising video conferencing with early career researchers “because of its richness in terms of cues – physical presence, voice inflection, but especially body language”.

This is particularly important early in the mentoring relationship, as is having frequent contact, she said: “Don’t leave one meeting without setting up the next on your schedules.”

These kinds of meetings should be once or twice a month and, in the interim, be sure to keep up via email, she said.

For Dr Tigges, it is important to recognise that early career researchers are under particular stress during the current crisis. “Their research may be on hold because of stay-at-home orders or social distancing constraints; this may cause significant anxiety because of tenure and promotion timelines...They may be having to learn to teach online for the first time, and that will distract from their research activities,” she said.

In addition, many may be dealing with competing demands, such as childcare or other family members affected by the crisis.

“Make time at the beginning of meetings or in all email exchanges to ask them how they are, how they are juggling commitments, unique stressors they are facing,” she advised.

It is important that senior faculty support early career researchers by advocating for the extension of promotion and tenure timelines and extensions of deadlines within their institutions. As is emphasising the need for a “balance between personal and professional needs − it may be that personal obligations need to be the priority during this time”, she said.

Finally, she said senior mentors should recognise that their early career mentee “may be more proficient than you with technology and ways to stay connected from a distance. Ask them if they have ideas about how to best work together”, she said.