Has the pandemic changed research culture – and is it for the better?

Source: Getty montage

After more than a year of the Covid crisis, the old ways of working for many people seem like a distant memory – and research is no exception.

Travel restrictions have forced international conferences online and prevented overseas fieldwork. Lockdowns have sometimes made access to vital research facilities impossible. And the closure of schools and nurseries has forced academics in general and women in particular to juggle their workloads with childcare.

But alongside these practical upheavals, and perhaps as a consequence of them, there has also been a quiet revolution in the way that researchers collaborate and disseminate their findings.

Sparked by the need to quickly get to grips with the scientific and social impacts of the crisis, the use of preprint servers has accelerated, while new interdisciplinary networks and links to policymakers are springing up, fuelled by fevered social media discussion around the latest public health developments.

The big question is whether such developments are permanent. Will everyone revert back to the old ways of working when Covid finally fades into the background? Or has the pandemic prompted or catalysed changes that will endure?

For one UK academic working in public health, the “new and better collaborations” that have been established between academia and medical staff on the front line is one of the clear benefits of the crisis.

“I work in a large university centre that studies National Health Service records to help improve public health,” explains Jessica Butler, a research fellow at the University of Aberdeen Centre for Health Data Science. “Pre-pandemic, we worked separately from the NHS, with the university staff doing research and the NHS staff focused on audits and reporting.” But now academics are at the forefront of developing applied solutions to help the NHS, such as modelling local hospital occupancy or analysing patient vulnerability to aid the vaccine rollout.

“It’s been tremendously rewarding to have our work be necessary and immediately useful. And it would be against public benefit to go back to our traditional ways of working,” Butler says.

Nor is it merely in the most obviously Covid-related disciplines that things have changed for the better.

Romesh Vaitilingam, editor-in-chief of the Economics Observatory, says the urgent need for solutions has seen direct lines established into the heart of government. The observatory was set up last year to help connect academics with policymakers and the public on the economic issues for the UK raised by the Covid crisis; users can post a question and the observatory attempts to answer it by commissioning an article from an expert.

“In terms of academia and policymakers, there’s been a big boost,” Vaitilingam says. “Government departments have been consulting economists and other researchers on the whole swathe of questions raised by the crisis.” And he suspects that, post-Covid, “engagement will continue around other pressing global concerns, such as climate change”.

Interdisciplinary collaboration has “understandably” been a feature of the pandemic too, adds Vaitilingam, with interaction between economists, epidemiologists and public health experts being central to the response.

However, much of this collaboration has taken place against the backdrop of national responses to the pandemic. Does that mean international academic collaboration has been dented – particularly given the travel restrictions?

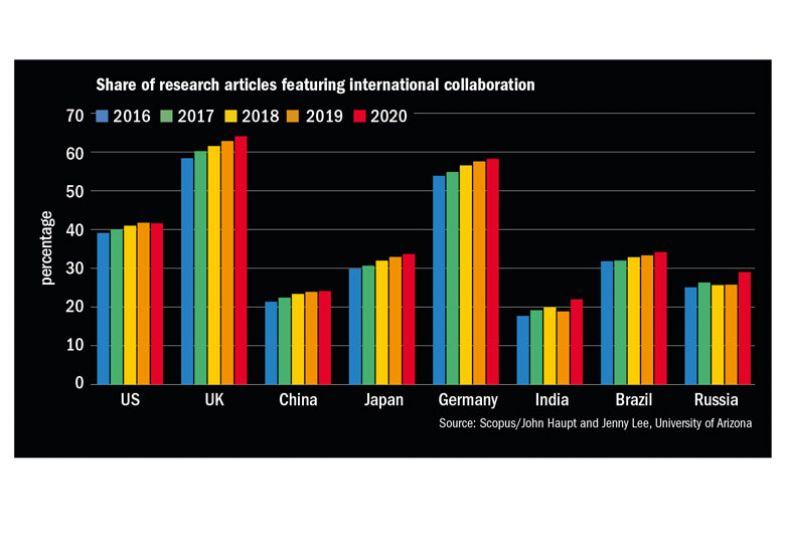

The evidence so far suggests not, according to John Haupt, a graduate associate for assessment and evaluation at the University of Arizona’s Center for the Study of Higher Education. The latest data he has compiled – alongside Jenny Lee, professor of higher education at Arizona – suggest that 2020 saw another increase in the share of nations’ research output that featured overseas collaboration. And that was true for high- and low-income countries alike.

Haupt points out that most papers published in the past year that aren’t directly related to Covid-19 probably derive from projects that began prior to the pandemic and that continued remotely. And even if international travel becomes less common post-pandemic, his hunch is that this will not have a significant effect on collaboration because global mobility “is only a part of what makes international collaborations possible. Researchers are most likely going to continue to pursue global lines of inquiry that were started prior to the pandemic and engage across national borders with colleagues who share similar interests and have complementary skill sets. The pandemic may have increased the number of global lines of inquiry as well.”

High energy physics is a field that, by virtue of its reliance on large international facilities, has traditionally seen extremely high levels of cross-border collaboration. Valerie Gibson, head of the High Energy Physics Group at the University of Cambridge, says that while “there have been delays to the experimental programmes” at particle accelerators such as Cern in Switzerland, “data analysis and collaboration continues as before. We are very used to virtually collaborating and accessing data remotely.”

However, Caroline Wagner, Wolf chair in international affairs at Ohio State University, who has also followed collaboration patterns since the start of the pandemic, cautions that the effect of travel restrictions on the formation of new partnerships in less structurally international disciplines may be yet to emerge.

“As many as 90 per cent of international collaborations begin face-to-face or side-by-side, so I would expect to see a drop-off in international collaborative publications in the next three years, when the results of 2020 activities in research can be seen,” she says. “Collaborations may have been delayed or just not gotten under way because of immobility.”

The degree to which cross-border links will be re-established “depends in part on science policy”, Wagner adds, “since connections will likely need to be jump-started with targeted funds in order to get going again”.

One forum where many pre-pandemic collaborations were established is, of course, international conferences. And while some conferences have moved online, there are questions about whether even the most sophisticated software can replicate the opportunities for chance encounters offered by physical events.

The question, once again, is whether normal conferencing service will resume post-Covid – particularly in light of the mounting pre-pandemic concern about its environmental costs.

“I and many of my colleagues now appreciate getting together physically a lot more than we did before,” says Holger Hoos, professor of machine learning at Leiden University in the Netherlands. “It was a sort of given and now we don’t have that any longer we can see how valuable it actually has been in lots of ways.”

As well as the difficulties of replicating the social and networking aspects of physical conferences online, Hoos also points to the psychological difficulty of fully engaging with the presentations at virtual events. “It is far easier to just sign out whenever you feel it is getting a little too boring or to cherry pick and just go to things that you know are worth going to. And this is something I have heard from quite a few colleagues,” he says.

However, he still believes that conferences will move towards a “hybrid” model, offering the option to present virtually but also retaining the advantages of the physical meeting for those who want them.

Cambridge’s Gibson sees the same kind of shift taking place in high energy physics, too – although she warns that “we need to make sure that no biases creep in” against those who attend only remotely. “We also need to consider the etiquette of virtual meetings and how to introduce the community-building and networking aspect,” she adds.

If there is a permanent change to conference culture, another impact that needs to be considered is the knock-on effect on conference proceedings. Computer science, for instance, publishes a large proportion of its research in this format; of 2.1 million publications in the discipline between 2015 and 2019, more than half (1.2 million) were conference papers, according to Elsevier’s Scopus database. Mathematics (40 per cent) and engineering (36 per cent) also rely heavily on conference proceedings.

According to Hoos, that tradition may have originally derived from a belief that conference proceedings would be a quicker way to disseminate research than journals. However, he endorses the growing calls – led by one of the field’s most eminent scholars, Moshe Vardi of Rice University – for computer science to move away from this publication model.

“It probably means we will attend fewer conferences,” he concedes. “But when we do go, we’ll still get the benefits of the networking that happens there face-to-face.”

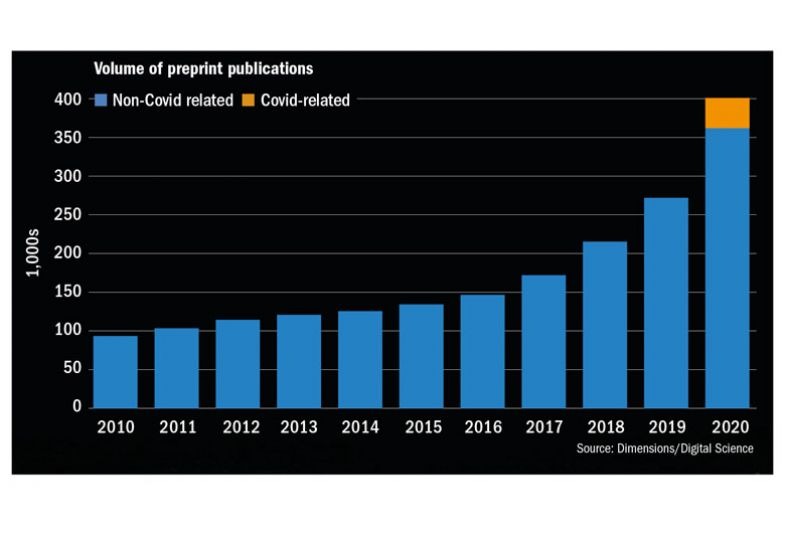

Another impact of the pandemic on publishing practice has been an acceleration in the use of preprints.

According to figures from Digital Sciences’ Dimensions platform – which includes data on both preprint and peer-reviewed journal articles – about 400,000 preprints were published in 2020, an increase of 47 per cent on the year before. Although the figures – published by Times Higher Education in January – make clear that 39,000 of these were Covid-related papers, the volume of preprints unrelated to the pandemic also grew by a third: a higher rate of increase than over the previous two years.

Samuel Moore, research fellow at Coventry University’s Centre for Postdigital Cultures, says preprints have been “a hugely important feature of the pandemic response effort and it has displayed the value of collaborative research processes in which researchers share their work openly and as early as possible”.

However, the increased prominence of preprints has also led to growing scrutiny of their use, with concerns that they may have promulgated numerous red herrings in the early scramble for answers on Covid. And even away from medical science, some academics worry that the lack of peer review in this expanding area of publishing is only going to make it harder to tackle issues such as reproducibility.

“If we circumvent peer review by publishing things as preprints, I think we encourage people to build on a less than solid foundation,” warns Leiden’s Hoos, who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research. “Personally, I can’t help but feel that this is problematic, especially in areas of computer science where the algorithms and systems you are dealing with…are very complex.”

For this reason, peer-reviewed open access journals like Hoos’ may come to be seen as a “best of both worlds” option post-pandemic, combining the accessibility of preprints with the rigour of traditional journals. However, Moore worries that, unlike the preprint servers that are largely “scholar-owned or governed”, open access journals are an area where traditional publishers, with their larger financial clout, are gaining too much control – at the expense of “the presses that are able to do open access ethically and equitably, such as university presses, scholar-led publishers and other not-for-profits”.

Aberdeen’s Butler agrees that the pandemic has clearly taught us that there is now “no justification for the slow, closed, biased and expensive for-profit model of disseminating research via private publishers”. She notes that journals accounted for little of the high-impact research published during the pandemic, such as the quick sharing of the coronavirus’ genetic sequence, the aggregation of Covid statistics on websites such as Our World in Data, and the software developed to model the spread of the pandemic. And she still hopes that the biggest long-term academic impact of the pandemic will be “a move to rewarding research beyond articles published in old-fashioned journals”.

That issue of reward, of course, is the key one – especially for early career researchers trying to establish themselves.

“Until we make that reform, and couple that with how we reform publishing, young scientists are always going to feel pressured to play the game,” says Scott Rich, postdoctoral research fellow in computational neuroscience at the Krembil Research Institute in Canada.

Moreover, it is not only in publishing that the post-Covid flux in research culture could disproportionately impact junior academics, adds Rich. For instance, while moving conferences online makes them more accessible, he worries that it is hard to recreate the elements of physical events, such as poster sessions, that help early career scientists to showcase their work to other delegates.

“As much as academics complain about poster sessions, they are the closest to a meritocracy in a conference because the most interesting poster and engaging speaker is naturally going to attract attention, as opposed to just relying on a selection committee to decide your speaking slot,” Rich says.

Indeed, the lack of opportunities for junior academics afforded by online conferences has already emerged as a big concern in an ongoing study of the impact of the pandemic on early career researchers. Harbingers, originally a four-year project looking at all aspects of research culture among junior academics across several countries, has been extended for two more years by its funder, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, to track the impact of Covid. Its first UK respondents have reacted “mainly negatively” to the shift to online events, says David Nicholas, co-director of the research and consultancy firm, CIBER Research, which is leading the study in association with the University of Tennessee. “Many agreed that they could not develop new potential collaborators if they could not meet them first,” he says, adding that Harbingers had already identified this as an important mechanism for junior academic progression.

Other initial findings from Harbingers 2 include delays to research projects because researchers are unable to use their labs or, in the case of social scientists, conduct face-to-face interviews.

“Universities differed in how much they would let ECRs into the lab,” notes Nicholas, a former director of UCL’s department of information studies. “Some, for example, had one week [in] and one week at home, which did not necessarily fit in with the nature of their experiments.”

Harbingers 2 has also received early responses from France, where early career researchers were more open about the mental health issues they were facing, Nicholas says: “Some are very isolated in their lonely and very small apartments, and some of them clearly felt depressed, missing connections. Many…mentioned the fact that even if they were able to do research, their ‘creativity was broken down’. Because of the lockdown, many were wondering whether to continue with an academic career.”

Another major issue that has cropped up in Harbingers 2 affects academics at all levels. This is the difficulty juggling childcare with remote working when lockdowns have shut schools and nurseries. A raft of studies have suggested this may have had a particular impact on women’s research output, given other evidence from academia and further afield that the childcare burden has fallen more heavily on them.

The trend is clearest in preprints, given their short time to publication. The proportion of preprints with a female first author has dropped on servers including arXiv (which mainly covers physics and mathematics), bioRxiv and, in particular, medRxiv.

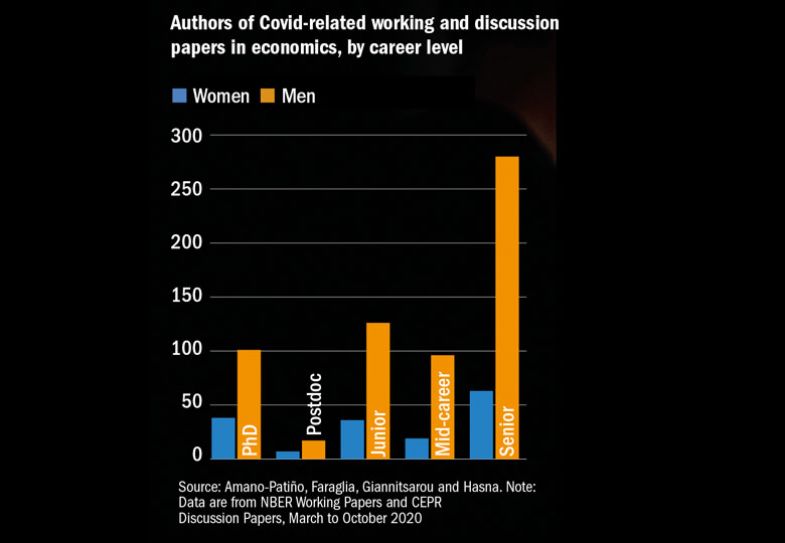

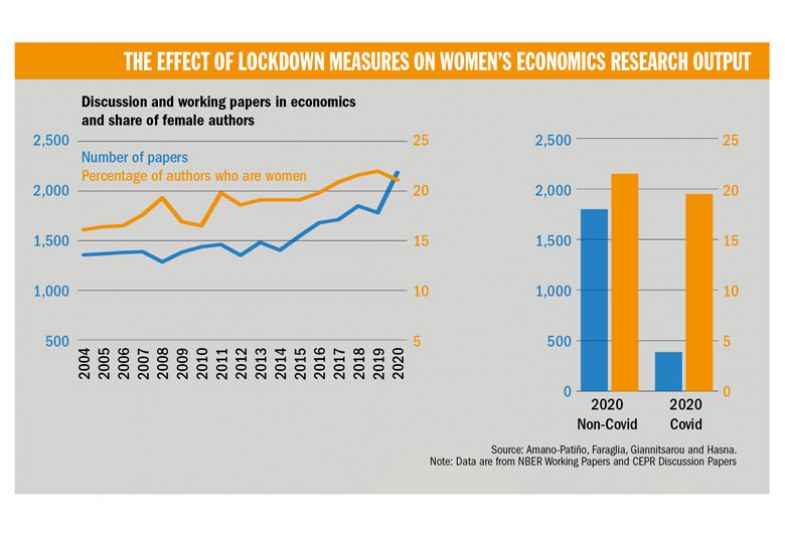

Another discipline to identify an issue has been economics. Noriko Amano-Patiño, assistant professor in the Faculty of Economics at the University of Cambridge – alongside colleagues Elisa Faraglia, Chryssi Giannitsarou and Zeina Hasna – identified as early as last April that women’s productivity could have been affected by the lockdown measures. Just one in eight authors of the initial explosion of Covid-related working and discussion papers were women, they found. And further analysis of publications through to October has backed up their initial findings, Amano-Patiño says.

“A striking statistic is that out of the 991 authors that have been part of the research groups that wrote the 386 Covid-related papers [published] from March to October 2020, only 19 are mid-career women academics,” she says. “Since Covid-related research spans many fields in economics – including applied microeconomics, which typically attracts relatively more women – it seems unlikely that this gender divide could be due to a relative lack of interest in Covid-related topics among women.”

Amano-Patiño fears that in the absence of specific interventions, women in her discipline are “likely to fall even further behind”. And this matters not only because of its direct impact on gender equality, but also because it could lead to less robust and balanced research – which, in turn, will affect the decisions that politicians make in response to the Covid crisis.

One of the researchers who has analysed authorship in pure science preprints hopes that the patterns identified during the past year will act as wake-up call to universities to “make much more substantial investments in high-quality, affordable, safe childcare options for students, postdocs and principal investigators”.

But Megan Frederickson, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, worries that “once schools and childcares fully reopen and the pandemic-related childcare crisis has passed, academia will just revert to its pre-pandemic policies and culture, instead of making lasting changes”.

Nevertheless, Frederickson hopes that the pandemic will prompt some reflection on how certain groups within the academy are disadvantaged by attempts to measure excellence in the standard ways: “I think ‘publish or perish’ will likely always be part of academia, but I do think we academics need to start looking past the quantity of a researcher’s publications and find better ways of assessing research excellence when we make decisions about hiring, tenure, promotion, grants and awards.”

Indeed, many academics are likely to endorse her hope that one positive legacy of the pandemic will be a more sustainable research culture for everyone involved.

Rich, the postdoc, adds that as in “all elements of life, the pandemic has shone a spotlight on problems that already existed because it exacerbated them. The pathway for early career scientists is so risky and so fraught and so tenuous: all that was thrown into stark relief by Covid-19.”

However, he adds that whenever this has been challenged in the past, the answer was always: “That’s the way it is and that’s the way it always will be”.

“In a best-case scenario the pandemic shakes people out of that haze,” Rich concludes. “Hopefully, this is that break in the system.”