For all its political instability, arid climate and dwindling oil reserves, the Middle East and North Africa is often considered to harbour significant economic potential.

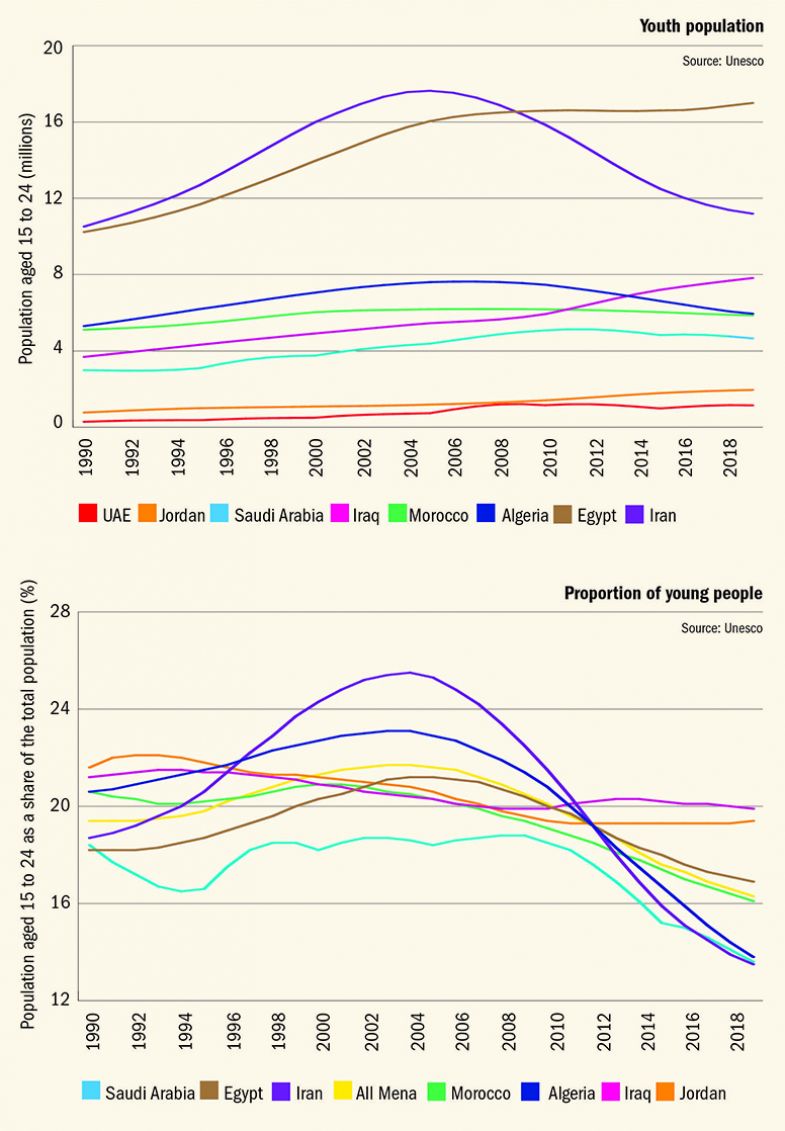

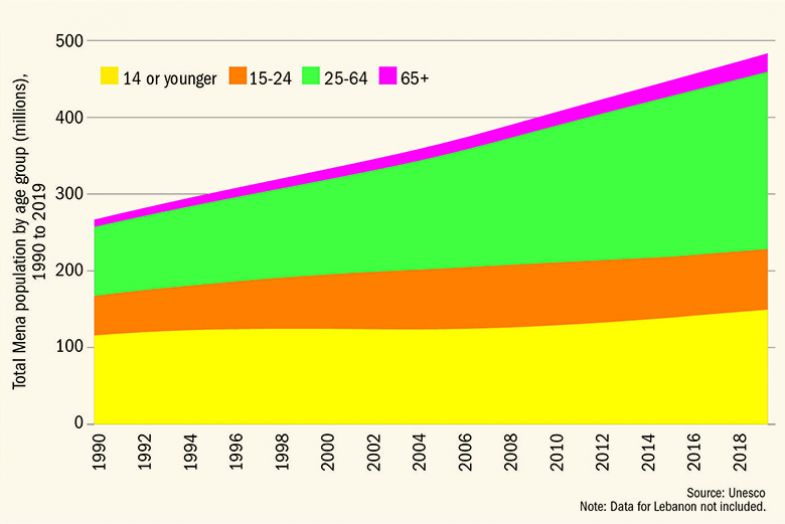

Such optimism derives from the region’s relatively large youth population, which is increasingly being educated to a high level. The number of people aged between 15 and 24 in the Mena region has risen by about 60 per cent in the past 30 years, and also grew as a proportion of the overall population, a figure that is regarded as a key marker of development potential.

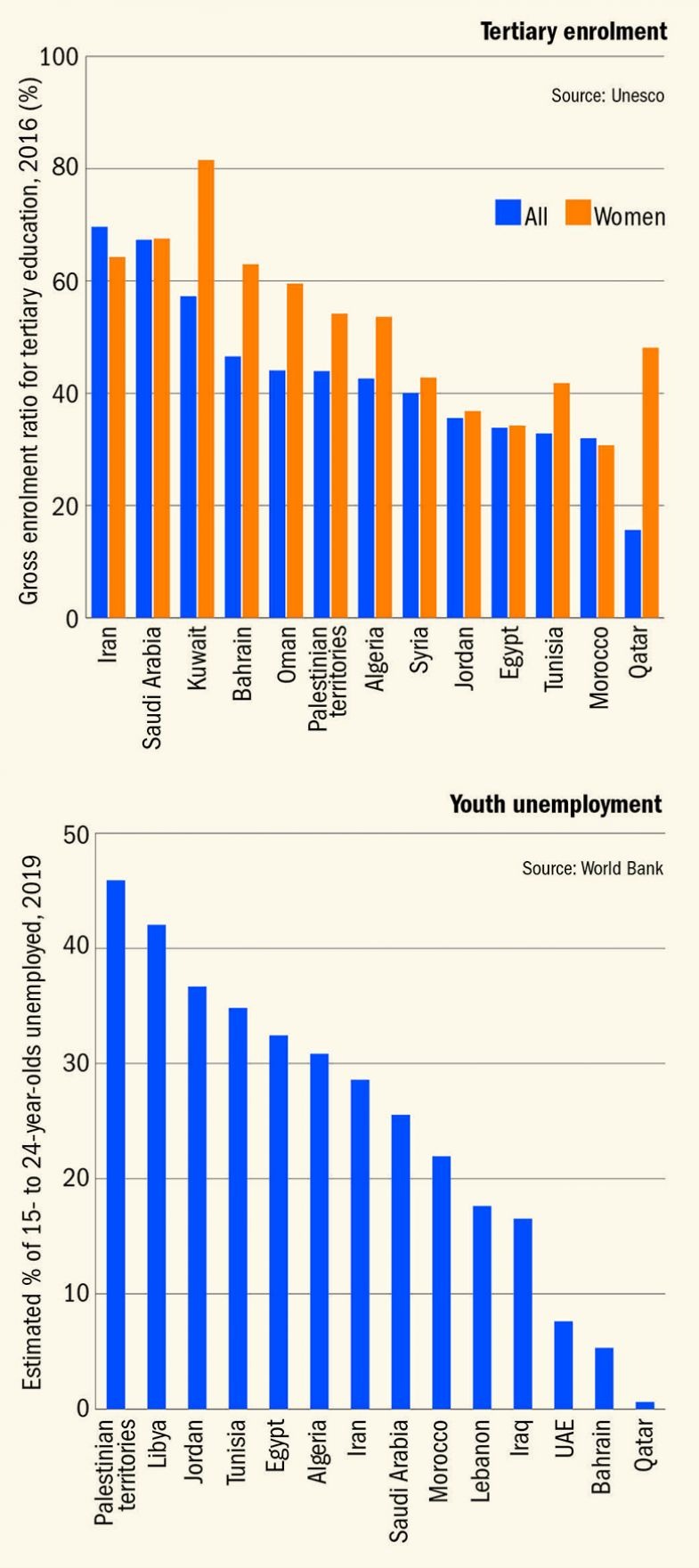

The growth has levelled off over the past decade, and even begun to decline in some countries – most notably in Iran, the region’s second most populous nation. However, an increasing proportion of young people are accessing higher education. The region’s gross enrolment ratio (GER) – the number of people in tertiary education as a share of all school-leavers – is about 40 per cent: a similar figure to East Asia and way ahead of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In Iran and Saudi Arabia, the two Middle Eastern superpowers, the GER is now close to 70 per cent.

But the picture is not all rosy. The major challenge facing nations hoping to capitalise on their well of young human capital can be seen in the labour market statistics. Overall, estimated unemployment in the region is almost 10 per cent (for comparison, it is around 6.5 per cent in the European Union and just under 4 per cent in the US) while for young people it is over a quarter (compared with 16 per cent in the EU and 8 per cent in the US). Perhaps most worryingly, data suggest that unemployment can also be very high among people with a university education: the rate is around a fifth in Egypt, for instance.

Of course, there are exceptions, most notably in the wealthy Gulf states. In the United Arab Emirates, only 8 per cent of 15- to 24-year-olds were unemployed in 2019 and in Qatar the figure was less than 1 per cent. But these are small nations, and the much higher level of youth unemployment in more populous countries such as Saudi Arabia (26 per cent), Egypt (32 per cent) and Iran (29 per cent) raises a major question: is this growing pool of graduates leaving university with the right skills to drive economic growth in the region?

For Chris Davidson, an expert on the region and a former reader in Middle East politics at Durham University, a “common thread” across all Mena countries is their long-standing struggle to ensure that their higher education systems match the “needs of the economic agenda of the day”.

That agenda is now firmly focused on how to build economies that will continue to flourish once the oil wells have run dry – or been turned off amid a global switch to green energy. And although rulers and governments in the region have produced eye-catching flagship plans on how this will be achieved, such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, realising them could prove a Herculean task.

For one thing, it will involve a massive expansion of the private sector. However, universities in the Mena region have historically focused on the public sector, the traditional source of high-paying, graduate-level jobs – especially for those with a degree in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics qualifications that have traditionally been seen as the priority by students, parents and governments alike.

Davidson suggests that this science focus may need to change if Mena nations truly want to kick-start their economies.

“There has been, in general, a lack of the kind of liberal education that is going to produce graduates…capable of plugging into international business,” he says. “Evidence shows us that well-rounded graduates are the best performing graduates. So there needs to be a significant rebooting of humanities and social science teaching in many Arab countries.”

Hoda Mostafa, director of the Centre for Learning and Teaching at the American University in Cairo, agrees that a liberal arts approach could be the key, since it “allows for a broad base of knowledge and skills with an area of interest that can be explored at a deeper level”, allowing universities to “move beyond the STEM and non-STEM silos of thought and into a more interdisciplinary experience for our students”.

The problem, according to Davidson, is that while the Gulf states have the “resources to simply import that teaching model” through branch campuses of Western universities, that is a “luxury that other states simply don’t have”. Hence, “they are having to reform their non-STEM subjects from the ground up”.

But, even in the Gulf states, there are question marks over whether enough local citizens are taking advantage of the liberal arts education on offer. According to Laure Assaf, assistant professor of Arab crossroad studies and anthropology at NYU Abu Dhabi, “if you look at what type of subjects…families are pushing the youth to study and what sectors the government is also promoting, they are very much the sectors that around the Middle East are recognised as the most valuable sectors of employment, and those are engineering and science.”

That “bias” is even more evident in Mena countries that have older national universities, she adds: “In a place like Egypt or Jordan, your ability to access engineering or science and to access the humanities really depends on your grades in high school. All the good students are encouraged to go into medicine, architecture, engineering, etc.”

As for branch campuses, many in the Gulf largely educate international students. Davidson’s latest research findings – as yet unpublished – suggest that they are producing a “mere trickle” of domestic graduates. “An even smaller trickle appears to have gone into anything other than traditional public sector jobs,” he adds.

A changing population

Subject mix is not the only issue. Other observers suggest that teaching approaches across all disciplines need to change to produce more adaptable graduates.

One of the region’s most prominent scientists, Rana Dajani, associate professor of molecular cell biology at Jordan’s Hashemite University and president of the Society for the Advancement of Science, Technology and Innovation in the Arab World, says she has used some of her classes to show students how to design websites or communicate science in the media, for instance.

The vision of any university, in her view, should be to produce graduates “who can [use] their skills and knowledge that they gained to make a difference in their own community”. This involves encouraging entrepreneurial thinking – although not in the “narrow-minded” sense that a business school might promote. Graduates will then be equipped to forge their own professional trajectories even if traditional career pathways are no longer available.

However, “most universities in the Arab world are very technical, very textbook-[based] and not connected to the actual needs of society”, laments Dajani, who is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Richmond’s Jepson School of Leadership in the US.

Marko Savic, a senior manager in international relations at the UAE’s Higher Colleges of Technology, echoes Dajani’s view that transferable skills, such as writing and critical thinking, need to be incorporated into disciplinary teaching, rather than being mere add-ons. However, from his experience of the UAE, “most universities teach those skills [separately], in silos...That kind of approach does not result [in] the job-readiness that employers are expecting.”

But how realistic is it for Mena universities to transform a pedagogical model that they have espoused for decades?

Dajani says it may be that only completely new, independent institutions could forge the right path; she highlights the work of small, fledgling colleges such as Jordan’s Institute of Critical Thought, which offers short, liberal arts-style seminar courses. However, she accepts that, in reality, such institutions will remain out of reach for the vast majority of students – who may, anyway, be drawn to the greater prestige of established universities.

The key, Dajani says, is to appoint young leaders – departmental chairs, deans and presidents – who have either been “exposed to the world...so they are not stuck in their local mindset” or are from minority groups – most significantly, women.

Mena population growth

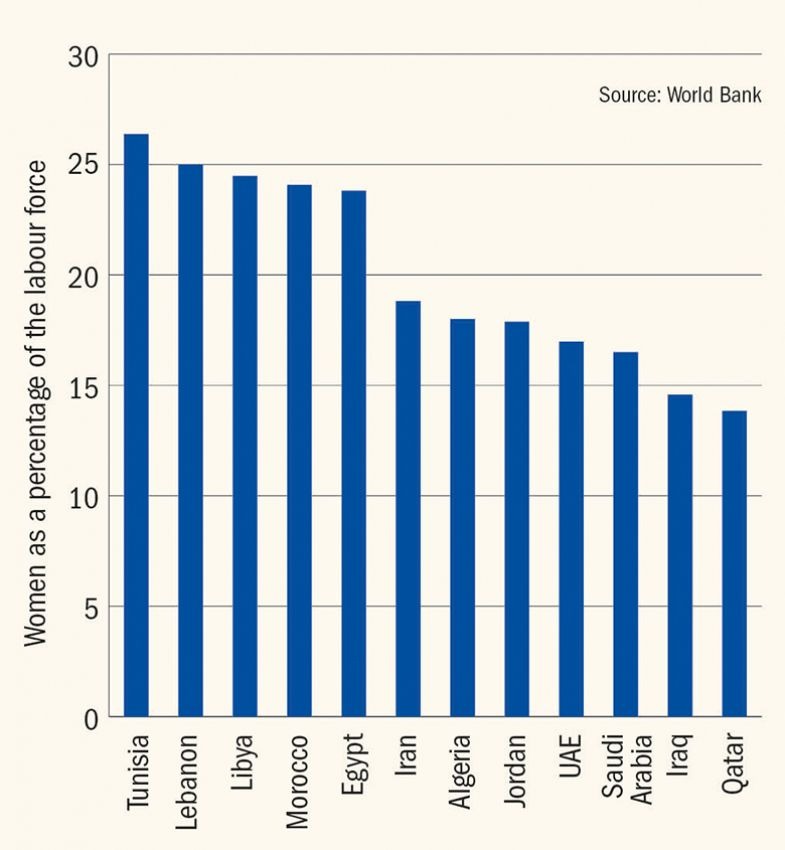

Indeed, there is an argument that even if established universities can shift their offerings to start teaching more transferable skills, the desired growth and diversification of Mena economies will not happen without major economic and social reform in the region – beginning with the role of women.

In many Mena countries, a notably high share of women go to university: the GER for women in Saudi Arabia is 68 per cent and for Iran it is 64 per cent (although it lags behind in Egypt, Morocco and Jordan).

Strikingly, women in these countries often study the STEM subjects that, in the West, are dominated by male students. An analysis of data from the Times Higher Education World University Rankings has shown that even in engineering, the share of female students in some Mena nations is much closer to parity than in Europe or North America.

However, the challenge is to harness these skills in the workplace. In almost all Mena countries, women make up less than a third of the labour force, far lower than elsewhere in the world. In Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan and Iran, women account for less than a fifth of workers.

Those with knowledge of the region differ in their views of whether this is down to women choosing to stay at home to look after children out of a sense of social and cultural responsibility, or being forced to do so by parents, husbands and religious authorities.

Davidson says that even when women graduate with first-class honours, their parents can be “unwilling to have them working in a male-dominated environment. They come up against this enormous cultural barrier, which is most extreme in Saudi Arabia but is there in varying degrees even in a country like Tunisia [which is thought of as more gender-equal].”

Indeed, in Saudi Arabia, the reach of the religious establishment extends even to university curricula. That is why, Davidson says, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has been trying to follow the UAE’s example and “restrict the influence of the religious establishment, not just in society but also in education as well – because he knows that...thousands and thousands of religious studies graduates are not going to contribute to his Vision 2030 post-oil future”. And rulers like the Crown Prince “very much like to identify themselves as guardians of educated women”, possibly because they are aware of the “huge reservoir of talent” they represent.

For Dajani, a major part of the problem is that, across the world, the modern workplace is organised to suit men without familial responsibilities, forcing women to try to work around that. The difference is that Arab women are “not ready to comply and fit into [that] mould. They would rather stay at home, and their culture supports them,” she says. “I think there should be equal representation of men and women in the workplace, but [women] should do it by choice,” rather than being forced.

She also questions whether women should have to try to shoehorn themselves into male career patterns, suggesting that it would be better if trajectories were redesigned to accommodate women who start their careers later, after childbirth. She also notes the possibility that highly skilled female graduates are already getting around this problem through self-employment ventures – often online or within the community – which are not picked up by official statistics.

The American University in Cairo’s Mostafa says that “more flexible, generous and adaptable parental leave policies” could encourage women to start post-university careers. She says that “innovation spaces” such as research parks could unleash significant economic potential if they were to adopt such policies and start employing women “who are highly educated and motivated to join the workforce”.

NYU Abu Dhabi’s Assaf says the situation “is really shifting because I think higher education is creating this aspiration among young women so they do want [their] education to be of use. Many of the young women I have interviewed…were very set on working and were even ready to shift their priorities” to enable that to happen. UAE policies to encourage more domestic citizens into the workforce have also “played in women’s favour”, Asaaf adds.

Nor are women – or men – in the UAE as focused on STEM as they once were, she adds. “The easy access to higher education and the fact that a lot of youth – and especially young women – have embraced this access...has created different types of aspirations. So you do have young people now who are dissatisfied with careers in engineering and would rather study arts.”

Education and unemployment

But is subject choice really the key issue in a region where it can be a struggle to find a job regardless of skill level or disciplinary background? In other words, what comes first in development terms: skills or jobs?

Mehran Kamrava, director of the Center for International and Regional Studies at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Relations in Qatar, agrees that while “it doesn’t seem as if the study of fields such as culture and politics is as much dismissed as wasteful as before”, the problem remains that “there are not enough jobs available...to absorb the increasing number of university graduates”.

The obvious solution, he says, is “for the state to foster employment creation schemes”. However, he laments the fact that, as far as he knows, there is no “meaningful” coordination between universities and the state in any Mena country that could allow such symbiosis to occur.

The Higher Colleges of Technology’s Savic agrees that it is impossible to analyse the whole problem without thinking about the interaction between governments, the economy and higher education. The “national priority” of states should be “to establish a triple-helix framework (education-industry-government) in order to build a functional and self-sustainable education-to-employment ecosystem”, he says.

Perhaps the UAE is ahead of the curve here. Davidson points out that it is “really putting resources into canvassing employers – and [government] ministries too – to try and work out what sort of graduates they really want”. However, he admits that it is much easier for a wealthy nation to do this than for a poorer one.

Working more closely with industry would also be an obvious way to improve employability, not merely in curriculum design but also, according to Mostafa, directly in students’ learning. For instance, students and researchers could be involved in collaborations with local industries and universities overseas to tackle problems unique to the region. She also sees a “unique opportunity” for the region to take advantage of the “explosion in entrepreneurship” that she says is growing among digitally engaged young people.

“Students entering higher education are very aware of the fact that the job market is changing. They are constantly seeking out opportunities to engage with the entrepreneurship landscape and we have recently seen an observable increase in these opportunities, with summits, incubators and accelerator numbers rising in the region,” she says. As well as inculcating skills such as “effective communication, interdisciplinarity, creative thinking, critical thinking and collaboration” that will help their students take full advantage of the opportunities, universities should also provide “formal education about this emerging field”, Mostafa says.

Governments could also help by supporting students to top up their knowledge and skills after graduation, such as by accessing online courses or studying abroad, she suggests. “I feel confident that students probably know more than we think they know about the gaps [in their knowledge and skills],” she adds.

Women in the workforce

If governments, business and universities fail to work together in a region ravaged by instability, the risk is that an increasingly educated workforce will simply go abroad, something that Davidson points out has long been “a huge problem across the region”.

“A country like Lebanon, which has probably one of best higher education systems in the entire Arab world, has been plagued, very sadly, by enormous instability over many decades, so has had one of the biggest brain drains of all,” he notes. “Every few years or so there will be reports of people starting to return, then something will happen and the diaspora will start growing again.”

The Gulf states, though, are an exception “because the social benefits, as well as any economic benefits, are just so great being a citizen of one of those states, compared with living and working in the West, for example”.

Whether they manage to transition successfully to a post-oil knowledge economy remains to be seen. Even if they do, it is doubtful whether other nations in the region that lack such vast oil wealth will be able to follow their example directly. But it is clear that if the Mena region is to prosper over the coming decades, the necessary innovation must begin on the region’s campuses.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Tapping the wellspring of talent

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login