Does the study of anthropology inherently run counter to conservative values?

In the age of Donald Trump, many in academia are re-evaluating how their professions are perceived by an electorate that rejected the establishment. Additionally, Republicans of all stripes – establishment or otherwise – seem to have soured towards higher education, with 58 per cent of them reporting that they think colleges have a negative impact on the country’s direction.

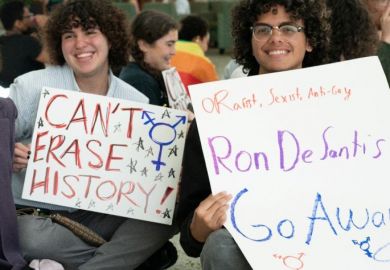

Anthropology – especially its various specialisations, which look at the intersection of evolution, race, sex, gender, colonialism, public land use, capitalism and climate change in different cultures – seems ripe for the picking if conservatives had to select a specific area of study to bash. And given how commonly it is offered as a general education option at various universities, how well it does or does not mesh with conservative students – and long-held conservative beliefs that predate the rise of Mr Trump, such as creationism – is something that anthropologists are paying attention to.

“I’ve gotten on one of my [course] evaluations that I’m not a scientist,” said Kimberly Kasper, an assistant professor at Rhodes College in Memphis. Dr Kasper was speaking on a panel addressing the teaching of anthropology in conservative states and environments, at the American Anthropological Association’s annual national meeting, held in Washington DC.

“[Teaching about] gender roles has definitely been an issue, especially for military spouses,” said Virginia Hutton Estabrook, an assistant professor of anthropology at Armstrong State University in Georgia, who was also on the panel. Cultural anthropology has been at the forefront of researching gender roles and how they vary across cultures, and Dr Estabrook mentioned military spouses as an example of a group that is typically strongly orientated around traditional US gender roles, when she teaches theories that may run counter to their views.

The session was less an airing of grievances than an opportunity to discuss strategies to bring conservative colleagues and students on board with anthropology and the various avenues that it explores. Scholars discussed the discipline’s relevance in race, sex, gender and evolution, specifically, and challenges and triumphs that they have had in teaching, especially in states across the South and the Midwest. Many described positive, if not exactly fruitful, relationships with students who opted for creationism over evolution.

“Alabama is the only state in the US that still has warning stickers on its [high school] biology textbooks [saying] that evolution is just a theory,” Briana Pobiner, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, told the audience. “The cultural context in which [anthropologists] are teaching is not very friendly.”

Still, both the panel members gathered to address teaching anthropology in red states and other conference attendees acknowledged that breaking down the discourse on higher education into liberal versus conservative, or Republican versus Democrat, does not always answer every problem facing anthropology’s role in academia.

Another panel addressed the “neoliberalisation” of campuses, not only in the US but across the world. Bipartisan pushes for privatisation measures on campuses, corporate influence on research and the pitching of higher education by policymakers as a practical means to better employment or boosting the national economy, critics said, puts programmes such as anthropology at risk, and obscures the purpose of education in the first place.

“They’re trying to pick the winners,” Cris Shore, an anthropology professor at the University of Auckland, said of policies in New Zealand and elsewhere, which prioritise science and engineering education.

While some speakers attributed recent trends to the increased political clout of populism, they also pointed to mainstream policymakers cutting back on education funding as a threat to anthropology and the humanities. Janine Wedel, an anthropologist at George Mason University, acknowledged populism’s dangers, but also contended that the same elites whom populists campaign against have also brought damage to academia.

Touching on themes that would be brought up in the session on teaching in red states, she said that anthropologists need to engage in domestic fieldwork. Part of the reason that the election polls predicting the outcomes of Brexit and the 2016 US presidential election were so off, she said, was because anthropologists and other researchers were ignoring their own countries.

“As long as we sit in our anthropological caves…we’re doomed,” Professor Wedel said. “If you don’t know anybody who voted for Trump [or Brexit], you shouldn’t be part of the conversation.”

The entire conference wasn’t all doom and gloom, however, as Marc Kissel, a lecturer in Appalachian State University’s anthropology department, tried to make clear. Building on other professors’ insistence that it was important to find a way to let religious students know that learning anthropology didn’t have to mean having one’s faith attacked, he said that there was room for both religious conservatives and anthropologists – plenty of whom, panellists pointed out, are religious themselves – to learn from one another.

“My postdoc was sponsored by anthropology and theology, and I spent a lot of time working with theologians,” said Dr Kissel, who did postdoctoral research at the University of Notre Dame. “The upshot is that I learned that theologians are not creationists, and they learned that anthropologists are not Richard Dawkins.”

This is an edited version of a story that first appeared on Inside Higher Ed.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login