Is it better to be a university dropout or to not have gone to college at all?

While there are often very good reasons for leaving university early, many worry that having “some college, no degree” on their job application will result in their CV being moved to the bottom of the interview shortlist pile.

Those university non-completers might wonder if they should have been advised to plunge straight into the job market rather than face a lifetime of explaining why they failed to graduate.

However, university dropouts should not write off their time on campus because even a small amount of time in higher education is likely to improve a learner’s life chances, according to a study published in Higher Education Quarterly this month.

While dropouts may fret about the stigma of leaving university early, they are far more likely to be in employment or in “top-level” managerial or professional positions than those who never enrolled in higher education, according to the study by Sylke Schnepf, associate professor in social statistics at the University of Southampton.

Titled “How do tertiary dropouts fare in the labour market? A comparison between EU countries”, the paper analysed non-completion rates for 15 European states using data published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).

In the Republic of Ireland, for instance, 76.8 per cent of those who left university before graduating – and never returned to higher education – are in employment, compared with just 65.4 per cent of those who left school at 18 – a difference of 11.4 percentage points.

In Italy, 83.7 per cent of permanent dropouts are in work, compared with 69.3 per cent of those with no tertiary education – a 14.4 percentage point difference.

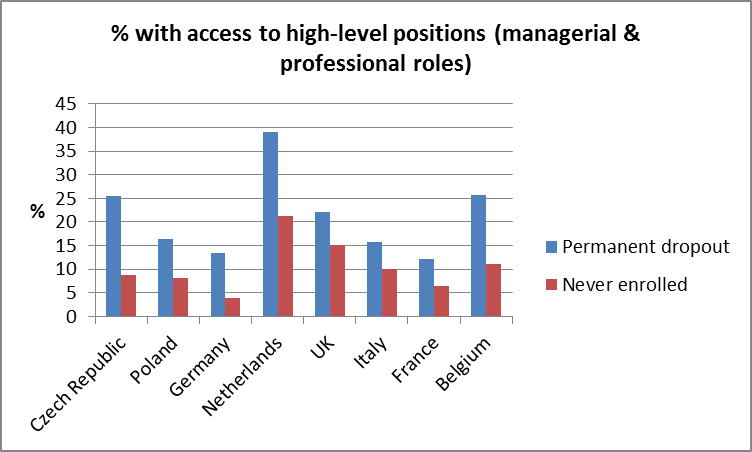

Disparities between university dropouts and those with no higher education are even greater if access to “top-level roles” is considered, says Dr Schnepf.

In the Netherlands, 39.1 per cent of dropouts held “top-level” roles, compared with just 21.2 per cent of those who never enrolled in higher education – 17.9 percentage points difference. Overall, the average difference on this measure across European Union states was 10 percentage points (it was 7.1 in the UK).

“There is definitely a stigma attached to dropping out of university in many countries,” Dr Schnepf told Times Higher Education.

“However, there should not be stigma because you are still better off than those who have not accessed higher education at all,” added Dr Schnepf, who is also a researcher at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Ispra, northern Italy.

While the advantage of “some college” versus “no college” differed between countries, nowhere in the study did non-enrollers outperform university dropouts, she added.

“University dropouts tend to have higher cognitive skills and parental backgrounds than other upper secondary school graduates, which alone could explain their better career progression,” admitted Dr Schnepf.

However, the paper takes account of this inbuilt “selection bias” in favour of dropouts by comparing them only with non-university attenders with the same characteristics, such as cognitive skills, parental background and gender, she said.

Dr Schnepf, who herself left an undergraduate physics degree to study political science, said that “being a university dropout myself, I know there are certain assumptions” about those leaving before graduating.

“But there is a real lack of information on student experience and labour market outcomes, which are important for evaluating different education experiences,” she added.

For example, Dr Schnepf said that she learned much from her year studying physics that could be applied to her subsequent studies of politics and economics.

Very often, policymakers also ignore the fact that many dropouts do return to higher education, as she did, continued Dr Schnepf, whose paper is the first cross-border analysis of the employment outcomes of university dropouts.

Some 23.5 per cent of students in Denmark drop out, but 58 per cent of these people return to complete their tertiary education.

In the UK, a third (33.8 per cent) of dropouts later came back into the system to graduate, a similar proportion to Germany (37.7 per cent), Spain (38.5 per cent) and the EU average (38.2 per cent), says the study.

“Dropout estimates based on student cohorts paint an overly gloomy picture, since more than one-third of dropouts in fact complete tertiary education at a later stage,” reports the paper.

The results may encourage more students to undertake higher study because the economic benefits of even a curtailed university education are clear, said Dr Schnepf.

“If students are hesitating about university study because they are worried about getting through the course, these results indicate that they should give it a try,” Dr Schnepf said.

Dr Schnepf added that penalising institutions for having high non-completion rates – as is proposed in the UK’s teaching excellence framework (TEF) – might also be unwise because it interprets dropping out as “personal failure and time-wasting”, whereas the reality is more complex.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login