The arrival of westerners in Mauritius at the end of the 16th century clearly did not do the dodo many favours. But the island nation’s government hopes that the foreign higher education institutions flocking to the Indian Ocean outpost will have an altogether more benign effect, on both local and international students.

It is easy to see why Mauritius might be an attractive place for Western universities to set up a satellite campus. Its government has long had ambitions to turn the island into a regional “knowledge hub”, and has made the processes of obtaining accreditation and visas relatively straightforward. The infrastructure is good, the official language is English (although a complex colonial history means that French is also widely spoken) and the country was ranked number one in the Ibrahim Index of African Governance in 2015.

Furthermore, while the island, located to the east of Madagascar, is geographically part of Africa, its population is largely of Asian origin (predominantly Indian but with a significant Chinese minority). This puts it at the crossroads of a range of important higher education markets. And that is not to mention the obvious attractions – the beaches, the cocktails, the landscapes and the weather – that have made Mauritius such a magnet for upmarket tourism.

There’s no arguing with the beauty of the sea and mountain views available from the upper floors of the building in Vacoas-Phoenix, where Middlesex University’s branch campus is located. Opened in 2010, it was the pioneering British venture on the island. To date, says its director Karen Pettit, it has offered a relatively small selection of the degree courses available at Middlesex’s base in London, namely “the popular programmes in most disciplinary areas”: business, law, psychology, education, advertising, media and computer science and IT. About 40 per cent of its current cohort of close to 1,000 students are international, from nearly 30 different countries. Africa – particularly Nigeria, Botswana and South Africa – is the biggest overseas market, and the campus has been actively recruiting in the Seychelles, the popular honeymoon destination about 1,000 miles to the north, where some of the courses that Middlesex offers simply aren’t available.

“Middlesex doesn’t compete directly with local [Mauritian] universities since they are heavily subsidised,” Pettit says. “But we recruit those [local students] with global aspirations, at fees just less than half what they would be paying in Britain.” Not only do British degrees have international currency, they are also seen as producing highly employable graduates who are “independent, autonomous thinkers with critical skills”.

For the future, Pettit hopes to gain accreditation for further undergraduate and master’s programmes, since “we need to diversify subjects and levels to increase student numbers”. The university recently announced ambitious plans to open a purpose-built new campus at Flic en Flac that could eventually accommodate 10,000 students (see artist’s impression, above). This will form part of the Education Village created within one of the government’s new “smart cities” by the Medine Group – a major local company that started a century ago as a sugar estate but has now diversified into property, tourism and education. There is already an International Campus for Sustainable and Innovative Africa at nearby Pierrefonds, where some 500 students study at branches of elite French grandes écoles and business schools, such as the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Nantes, École Centrale de Nantes, Université Panthéon-Assas and the Vatel management school. These offer bachelor’s and sometimes master’s degrees in architecture, computer science, consultancy, engineering, hotel management and law. Teaching is conducted in English, largely by staff flown in temporarily from the home institution.

Plans to develop pan-African education on the island also took a major step forward last year with the opening of the African Leadership College, set up by Ghanaian entrepreneur Fred Swaniker (see 'Pan-African appeal: the African Leadership College Mauritius' box below). Yet the government’s rush to develop Mauritius as a knowledge hub has also encountered a number of problems, both for the country itself and for incoming institutions, so it is worth looking at what has gone wrong and what is being done to put it right.

The University of Mauritius is located on a hill in the village of Moka. It seems to have grown rather haphazardly, with buildings of different eras all set at different angles and an unlikely main entrance down a turning off the route into the interior car park. Incorporating an existing School of Agriculture, it was officially established in 1965, three years before the country became independent from the UK, and it remains the largest university in Mauritius, with more than 12,000 students.

Indeed, it was still the island’s only university in 1988, when the Tertiary Education Commission was established to oversee accreditation and quality control – although the body’s remit also encompassed the Mauritius Institute of Education (for training teachers), the Mauritius College of the Air (for distance learning) and the Mahatma Gandhi Institute (a joint venture with the government of India focusing on Asian culture). Things have changed beyond recognition since then. Three new publicly funded universities have been established since the turn of the millennium: the University of Technology, Mauritius (2000), the Open University of Mauritius (2012) and the Université des Mascareignes (also 2012), which offers joint degrees with the University of Limoges in France. Even more significantly, more than 50 private institutions, mostly “local counterparts of overseas institutions”, are listed on the TEC website as having “joined the [Mauritian] tertiary education sector in the past few years”. Most have accreditation arrangements with British universities and professional institutions, although some Australian, French, Indian, Malaysian, Pakistani and South African institutions are also involved.

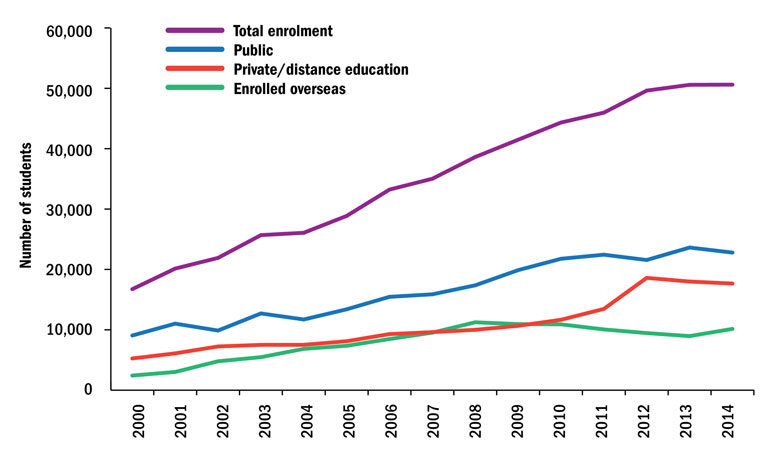

On one level, all this is obviously welcome. The main goals of the “knowledge hub” are to increase the numbers of institutions operating in Mauritius and to increase enrolment numbers, and the figures have certainly been going in the right direction. The total student cohort has risen from less than 17,000 in 2000 to more than 50,000 in 2014 (see graph below). Yet such rapid growth amid a regulatory framework designed for very different times was always likely to lead to problems. And so it turned out.

For one thing, most of the coverage is in fairly predictable areas, such as management, accountancy, medicine, dentistry and IT, leading to gaps, duplication and tough competition.

Getting established in Mauritius was certainly not plain sailing for the University of Wolverhampton. In 2014, a year after it set up a satellite campus in Mauritius, its registrar and secretary at the time, Helen Lloyd Wildman, marked the opening of a new building by expressing the hope that it would become an “African hub, attracting students from across the continent”. It recruited about 140 students on courses such as law, education and sports management, but 18 months later vice-chancellor Geoff Layer announced its closure. “The university has taken the decision to focus on its UK campuses and transnational education partnerships, rather than operate branch campuses,” a statement explained. (The university declined the opportunity for further comment.)

Mauritian participation in higher education

Source: Tertiary Education Commission of Mauritius

Meanwhile, Aberystwyth University opened its first branch campus in Mauritius last year, after being introduced to a group of investment partners at a conference in 2013. It has now moved into a new purpose-built site with capacity for up to 2,000 students.

“Lots of students want to study here for a UK degree,” says David Poyton, dean of the campus. “Our branding is that we can provide quality British HE, exactly the same as at Aberystwyth, for roughly half of what you would pay in the UK. We are selling both quality and status, in a country where many franchise degrees are available, with an international faculty and student body.” Twelve African states are already represented among the students, he adds.

Aberystwyth’s ambitions may yet bear significant fruit, but it was hardly a good omen when, earlier this year, its former vice-chancellor, Derec Llwyd Morgan, described the project as “madness” after it emerged that the initial enrolment in its first two terms consisted of a mere 40 students.

Mauritius itself has also suffered from the rapid expansion of institutions. Sushita Gokool-Ramdoo, who worked at the TEC until earlier this year and is now employed in the private sector, has a number of concerns. She fears that the knowledge hub risks “remain[ing] a knowledge consumption and regurgitation machine”, rather than genuinely improving Mauritians’ critical thinking. And she worries that “the growth of private provision in Mauritius is happening in a very haphazard way that does not necessarily respect the existing regulatory framework”. This has led to “some serious scandals”.

That critique seems to be partially accepted by the government. Deenesh Seeharry, an adviser at the Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research, explains that in the past “a few [foreign] tertiary institutions established offshore campuses [in Mauritius] without seeking authorisation from the regulatory bodies in their countries of origin. Hence, the qualifications awarded by these institutions were not recognised.”

In 2014, according to press reports, the TEC drew up a blacklist of 11 institutions, catering for about 1,000 students in total, which were not allowed to recruit for the following year. Most were said to be offshoots of Indian universities, although reference was also made to the Executive Business and Computational Institute and its “14 distance education courses [offered] in the name of the University of London”. (Asked for a comment, a spokesperson for the university stated that, currently, the institute “is teaching our programmes. The students are registered with the University of London through the University of London International Programmes and they take examinations that are both set and marked by the University of London.” The TEC website confirms that the institute is indeed now properly accredited.)

Such “scandals” also emphasised the need for legislative reform. The current government, which came to power after elections in December 2014, “had to find a solution for the students whose degrees weren’t recognised, and wanted to create a legal framework so the problem doesn’t recur”, Seeharry says. “The former minister tried [to introduce reforms], but the problem was in the timing [of the electoral cycle]. We didn’t make the mistake of waiting two years before getting into the reform business. No, we started on the first day.”

Mauritius’ major new higher education bill is designed to bring in “structural, pedagogical and legal reform”. Although it is still being drafted, earlier government statements give a good idea of what it is likely to contain. Higher education featured prominently in a speech given by prime minister Anerood Jugnauth in August 2015 to announce the creation of a “High Powered Committee on Achieving the Second Economic Miracle and Vision 2030”. He spoke of the country’s “immense potential as a regional hub for healthcare and medical services as well as a medical education centre of excellence for Africa”. And he hoped to see the higher education sector more generally “emerge as a strong pillar with robust growth. The confidence that we have built has enabled us to attract educational institutions of high repute from France…Thousands of foreign students are expected to be trained in our education hub every year.”

Some of the “key focus areas” flagged up in Vision 2030 also have implications for higher education. The government is intent on “transforming Mauritius into a smart island, by embarking on mega projects involving smart cities, new cyber cities including techno parks”. An Africa strategy aims to “position Mauritius as the regional platform for trade, investment and services to do business in Africa”. And a stress on “development of the ocean industry” includes the transformation of the capital, Port Louis, into “a modern port with state of the art facilities” and “a leading petroleum hub”, designed to cash in on “the 30,000 ships that pass by Mauritius annually to provide them with bunkering [ie, refuelling] and other related services”. This obviously raises questions about how the relevant skills can be developed.

“We now need proper legislation to regulate the whole sector,” education minister Leela Devi Dookun-Luchoomun told Times Higher Education, including “a proper independent quality assurance agency”, perhaps split off from the accreditation role of the TEC.

Many of the minister’s concerns focus on the public universities. She wants them to put greater stress on employability and “good collaboration between tertiary education [and] the world of work and industry”. She welcomes the fact that the University of Mauritius has just opened an office for knowledge transfer and would like to see the others producing more – and more directly applicable – research, which she may try to encourage with funding incentives. And she has asked universities to put scholarships in place for the specific purpose of staff development.

At the same time, the minister has no plans to create further public institutions, and she would welcome more private and foreign providers. She also offers some pretty broad hints about what she wants them to supply.

“At least five institutions are offering courses in management and IT,” she explains, “so we need to move on to applications of those skills and let people acquire other competencies and not do just the basic degree courses.” To avoid “overlap on a small island” and “duplication of resources”, she wants institutions to “collaborate and be complementary”. She also envisages a further push to diversify courses on offer in order to support “the new pillars of the economy identified under Vision 2030: ocean economy, bunkering, smart cities. We will need to get institutions which can deliver along these lines.”

Mauritius has major concerns about a brain drain, partly because many of its ambitious citizens go abroad to do PhDs and a significant proportion don’t return, despite incentives for them to do so. For this reason, the minister also believes that the country needs to “beef up postgraduate training and encourage some institutions to focus on such courses”.

So it is clear that there remain many opportunities for overseas universities to make a success of engaging with higher education in Mauritius. But, equally clearly, they will need to be ready to collaborate, adapt and respond to Mauritius’s economic imperatives. Otherwise, it could be the foreign arrivals that go the way of the dodo this time.

Pan-African appeal: the African Leadership College Mauritius

The African Leadership College Mauritius is “absolutely unique”, according to its head, Khurram Massod. “We already have close to 30 nationalities among our students. Few institutions, never mind universities, have that kind of pan-African diversity,” he says.

Now based on a lushly landscaped business park next to a rum museum in the district of Pamplemousses, the college forms part of the loosely knit African Leadership Network, created by Ghanaian entrepreneur Fred Swaniker. This has hitherto been best known for the African Leadership Academy in Johannesburg, which offers pre-university training to 200 potential young leaders at a time. But Swaniker wants to establish 25 higher education institutions right across the continent over the next decade or so. So why was Mauritius chosen to host the first, flagship institution?

The country is committed, responds Massod, to acting as “a hub for international education. Despite the ALC being pan-African, student permits and accreditation processes were easy to push through. Mauritius is stable and has trade agreements with almost every African country, so those coming from 52 out of 54 countries don’t need visas.”

It is still early days. The ALC does not yet have university status and the initial intake of 180 students is taking a foundation programme, developed with Glasgow Caledonian University, with a strong stress on pan-African themes and entrepreneurial leadership. But a new campus is already being built to receive 1,000 students in September 2017, with an eventual target of about 10,000.

Bachelor’s degrees, also accredited by Glasgow Caledonian, will start in January 2017. Business, computing and social science will definitely be on offer, with psychology to follow in September, and approval is being sought for engineering too. Also under development is a programme in “global challenges” that will allow students to choose from 16 key issues relevant to many African countries, such as education, infrastructure, poverty and urbanisation.

According to self-proclaimed “global Scot” Pamela Gillies, principal and vice-chancellor of Glasgow Caledonian University, her institution was chosen as a partner because of “our track record delivering capability enhancement in Africa”. This is demonstrated, for example, by a five-year partnership to improve the skills of employees of South Africa’s Transnet Freight Rail. She was impressed by Swaniker when he came to talk to her about “his dream of creating 25 new ethical leadership universities for Africa” and she “understood the value of not taking young Africans out of Africa”.

Students with limited skills in English are required to arrive at the ALC at least three months early for an immersion programme, at the start of which they stand in front of a fire and pledge not to speak any other language. It is mandatory for students to live as well as study together, since Massod believes in the value of “holistic learning and cultural activities”. It will also be mandatory for them to take on internships lasting about three months each year, preferably in their home countries. This is to address the “real gap in talent to solve local problems” from which African companies often suffer, obliging them to fall back on “importing people from abroad”.

Massod also hopes that students will return home with their “new ambitions and skills and networks” after they graduate. Yet “pan-African identity is so much in the air and the water here that even if they decide to go off and make their millions in the City [of London], I know that at some point they will contribute to solving African problems through their money or intellect”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Expanding horizons

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login