After a year of unprecedented disruptions and change, it is clear that, as the new semester approaches, students need better experiences, universities need better business models and staff need better workloads.

I split my career between industry and academia, encountering the academic world at many levels and locations and learning pedagogy from scratch at 41. As a result, I developed a hybrid mindset and often felt alienated (sometimes, alienating) in discussion with academic colleagues and senior managers.

The relentless simplifier in industry is to reduce any problem to cash flow, something deeply imprinted on all managers. On the single occasion I entered the director’s office seriously worried about my job, it was over a bid I was running. A senior manager felt the proposal showed too much risk: he wanted to rejig the numbers (fine by me) but wanted me to sign off his new picture (big problem). That it went to the director and that I kept my job shows how deeply embedded and widely spread this sense of cost and value was. You knew what the numbers were, and you took responsibility at all levels.

My observation on academic life was that because planning and module design were spread across departments and functions, nobody had a robust picture of what was happening or knew the full consequence of change. As a result, mythologies were propagated by everyone to everyone from new staff to vice-chancellors. I remained sceptical about academic cost collection and the conclusions drawn from it, and I would stubbornly try to work out the “real cost” of decisions whenever I could.

Why is this so critical to universities just now? The problems they face are not just about fast, radical change that must add up to a sustainable future; they are about what decisions need to be made, at what level and how to coordinate them across boundaries. I have come to admire the smart thinking of front-line teaching staff, but this distributed expertise is hard to harness to any central, but still distributed, planning process.

Some form of industrial thinking is needed, whereby those who teach and design modules apply a clear, if simplified, budgetary model. Is this possible?

Let’s explore a more industrial mindset, using the example of how affordable small-group teaching is for universities, online or in coronavirus-limited seminars. We may have to implement wholesale change to run them, but how viable are small groups themselves?

Imagine a UK institution that charges an annual £10,000 for 120-credit-a-year degrees, paying its staff an average £45,000 (which, with National Insurance and pensions, costs almost £55,000) for 60/40 teaching/research contracts. These figures are reasonable, but the trends they reveal should hold even if you change the details (and I hope you build your own model).

Let’s assume that the central administration consumes 60 per cent of the £10,000 fee but covers all other staff. My experience was that discussion about the size of any centre was shrouded in mystery, but we are probably being cautious if we allocate 40 per cent of fees to direct academic effort in teaching and learning.

A model for academic preparation and assessment completes the picture and shows that our fictional university has up to 55 academic minutes per credit per student per year to deliver undergraduate degrees. I would guess most ceilings are much lower.

Nobody ever wanted to discuss such a number with me! The nearest I got was a pro vice-chancellor who quietly explained that revealing a number like that would lead to all kinds of difficult conversations.

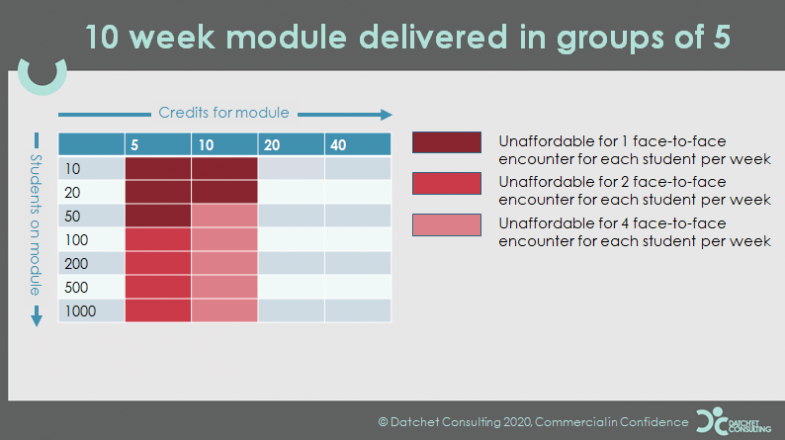

If a module is delivered over 10 weeks and students in groups of five have just one hourly encounter a week with an academic, you can work out the budget-breaking options in terms of number of students on the module and number of credits offered. Two encounters a week would bankrupt five-credit options; four times a week would do the same to the 10-credit options.

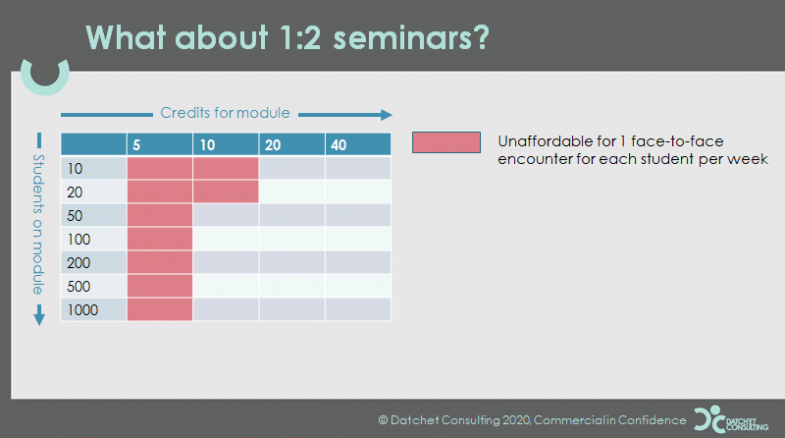

At the other extreme, weekly tutorials (two students per academic) are viable for all 20-credit or 40-credit modules, as well as large 10-credit modules.

This is a crude model – so be careful – but several conclusions emerge. First, modules that confer more credits while attracting more students support more affordable small-group options. So widespread use of small-group teaching in person or online is affordable, but – within the UK system, at least – will require significant module redesign to create the academic time.

If staff already running 20-credit (or more) modules with 100 or more students can make the case, good solutions exist for significant face-to-face education (online or in person). Creation of super-modules (eg, 40 credits, 1,000 students) would increase the options even further; a project management course run for all business and engineering students, for example, would play to scale in this way.

But even if, on tweaking the numbers, you reach different conclusions, my job is done. The point is that it will be hard to navigate this crisis without greater consensus and transparency on affordability. It may not come naturally to universities, but a more industrial mindset needs to be part of the new normal.

Terry Young is an emeritus professor at Brunel University London and the founder of Datchet Consulting. He worked for GEC and Marconi before serving as professor of healthcare systems at Brunel from 2001 to 2018.