By 1 May, member institutions of UK universities’ Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) will have to vote on whether they wish to formally bar any more of their number from leaving the scheme.

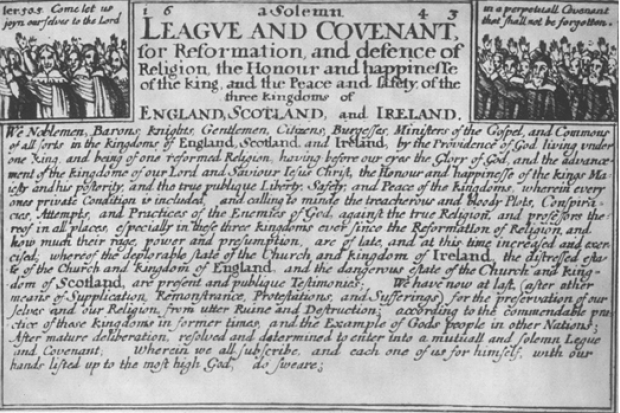

Plans for such a vote were already under way before the coronavirus pandemic put a further spanner in the works. The intention had been to protect the “covenant” – a feature of the USS that, in the eyes of many, makes it inviolate and, therefore, not subject to the same strictures from regulators as might apply to other schemes that run deficits of a similar size.

But Covid-19 certainly accelerated the USS’ actions. In mid-April, it issued a further “rationale” for action. The covenant, which represents the backing that members (“sponsoring employers”) could give to support the scheme through difficulties, would be weakened if those who were asset-rich were to leave. The USS had been looking over its shoulder at what had happened with Trinity College, Cambridge – widely regarded as “the last man standing” – which decided a year ago that its financial situation would be strengthened if it did not have to carry the contingent responsibility of supporting the USS.

Why the concern with the covenant? The scheme saw a fall in its assets of some 12 per cent in the first three months of 2020, while its liabilities are unlikely to have diminished – despite massive increases in government borrowing, the bond rates determining how these are discounted have scarcely moved. Did the USS believe that Trinity’s action would be contagious?

In its “rationale”, the USS suggested that there were many institutions that could afford to pay the so-called “Section 75 payments” that clear their obligations. Most of these appeared to be individual Oxford and Cambridge colleges. Hence, there were pleas for them, in particular, not to jump ship. Two “research-based” institutions were also considered well able to afford to leave. They were not named, but who they are is pretty obvious.

The USS is a voluntary association. USS sponsors joined it for their advantage, and, just as for any other club, they have the right to leave if membership no longer serves them. What they understood about the workings of a multi-employer plan when they joined the USS is difficult to fathom, and this aspect was not mentioned in the one authoritative history of the scheme’s founding at the beginning of the 1970s. Yes, the rule book did permit for rule changes to be made at the proposal of representative employers and members, but this permission was very general. Those who were faced with being blocked from leaving might feel at least as short-changed as members of open-ended investment funds who thought they could take their money out at will but who, like investors in Neil Woodford’s funds, found poor performance resulted in a moratorium on payouts and ended up losing shedloads of money (in fact, rules for such funds are much more explicit, and investors in them are more “experienced” than the institutions who signed up to the USS).

Breach of the covenant by leaving the scheme is seen to have serious implications. If more institutions followed Trinity’s lead, it would increase liabilities because a lower discount rate would have to be employed. Even to keep the USS on the path it wishes to follow, contribution rates would have to go up further. This is what all parties wish to avoid – all the more so in current circumstances.

However, trying to shut stable doors to prevent horses from bolting misses the point. PwC, which the USS employed to assess its strengths and weaknesses, described the covenant as “strong”, but also “on negative watch due to the risks of increased debt levels and strong employers exiting”. What PwC failed to comment on was another “strong” component of the scheme, “positioning of employers in the UK and global education market”. But Covid-19 has severely threatened the position of UK universities, along with those in countries, such as the US and Australia, that have been heavily dependent on high-paying foreign students. Even in the USS’ “rationale” document, this evokes barely a phrase.

What is really to be feared is a fall in the credit rating of the sector as a whole. In the past, some USS sponsors have had their status downgraded by Moody’s or S&P for overspending (especially on facilities) and overestimating student numbers. Some of the largest sponsors – research-intensive universities – are likely to find themselves in difficulties and downgraded because of their reliance on overseas (and especially Chinese) students. Examples include UCL, Imperial College London and the University of Manchester. Institutions such as these – which tend to have recognised credit ratings – are likely to be downgraded. They might not have been one of the last men standing, and they might not have been able to afford Section 75 payments, but their weaker position will dramatically affect the overall covenant.

Difficult decisions are unavoidable. The current remit of negotiators in the USS’ Joint Negotiating Committee, and the members of the Joint Expert Panel, established in 2018 after industrial action by academics over the threat of reduced benefits, has been to find ways to stay increases in contributions.

There have been proposals to remove “Test 1”, adopted by the scheme in 2014 to ensure that it remains within an agreed comfort zone of investment risk. However, this would encourage more “risky” investments. There have also been proposals to move to a “dual discount rate” – something to which the Pension Regulator makes no reference at all and that has the magic effect of making a sum of money worth one thing if looked at from one side and something else if looked at from the other.

It is time the negotiators’ remit became much wider – to look at the overall generosity of the defined benefits it promises, and at alternative models of risk sharing. Failing this, there might be no system left that is worth saving.

Bernard H. Casey is a retired USS member who also worked for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. He now runs a consultancy, SOCialECONomicRESearch, in Frankfurt and London.