The new intake of Oxbridge students beginning their studies this term is the most egalitarian for many years.

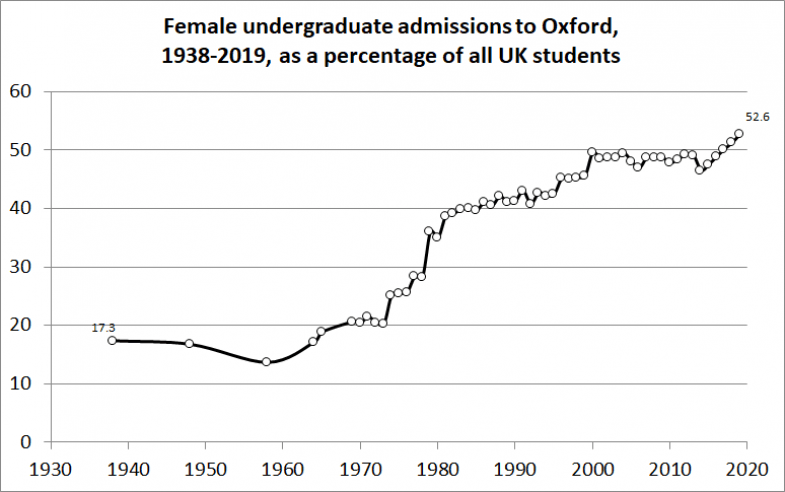

At Cambridge, a record 68 per cent of first-years are state-educated, while Oxford’s state school intake has also increased again, to 62 per cent. Oxford also admitted its largest ever share of female undergraduates this year – 53 per cent – and has pledged to admit a quarter of its intake from disadvantaged backgrounds by 2023.

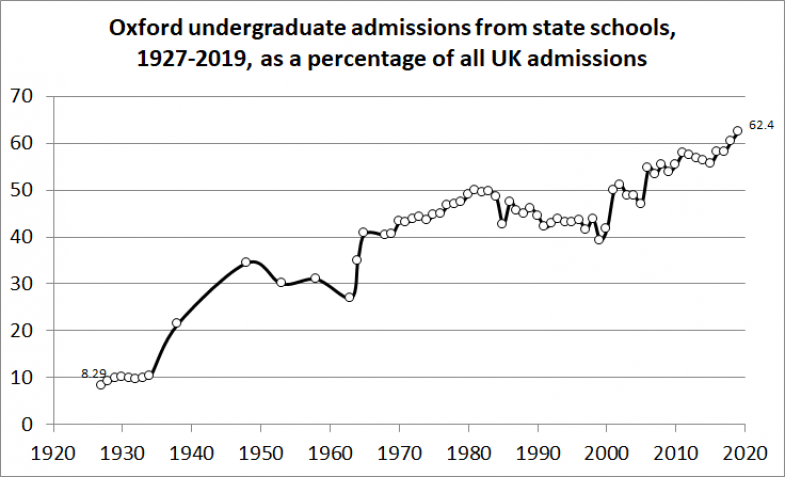

These institutions have come a long way from their origins as educators of elite men – in 1928, just 9 per cent of Oxford students came from state-funded schools – and a good proportion of that progress is attributable to changes in university policy. The fastest rise in the share of state-school admissions, for instance, occurred in the early 1960s, following the introduction of a standardised admissions form and entrance exam. This in effect ended the inequity of individual colleges having their own admissions procedures, which in many cases favoured certain leading public schools.

The eventual abolition of the entrance exam in 1997 was also followed by an immediate sharp fall in the proportion of private school students at Oxford. And although that was reversed the following year, after the government’s introduction of tuition fees, it resumed throughout most of the current century. The exception was between 2012 and 2015, following the introduction of £9,000 annual fees. Increases in the cost of tuition are likely to have a disproportionate effect on students from modest-income families, and this is an example of how the evolution of government education policy has also influenced Oxford admission patterns – more pervasively than you might expect.

The decision to admit many more women in the 1970s, prompting Oxford’s female quotient to rise from a fifth at the beginning of the decade to a third by its end, also had the unintended consequence of boosting its state-school admissions since the university tended to take more girls than boys from state schools. We’ve seen this trend again over the past three years, as Oxford has again admitted more women than men from state schools.

Another major influence on Oxbridge admissions from the 1950s was the division of English schools into two further categories: those that offered a three-year sixth form and those that offered only two years. The pupils perceived to be the most able in many private and selective state schools (mainly boys’ schools) stayed on after taking their A levels to undertake advanced work, including preparation for Oxbridge entrance. Evidence presented to a commission of inquiry in the early 1960s showed that these pupils enjoyed a significant advantage when they applied to Oxford – but it wasn’t until 1987 that this system was brought to an end by Oxford’s removal of the option to take the entrance exam post A level.

It is worth saying that, historically, the share of “state-educated” students at Oxbridge was higher than the admissions figures suggest since there were lengthy periods when a significant proportion of private school places were, in fact, mostly state-funded. According to the Sutton Trust, more than two-thirds of England’s top private schools were principally state funded up to 1976.

The Assisted Places Scheme had a similarly distorting effect on the figures between 1980 and 1997. This saw the government fully or partially funding private-school educations for more than 75,000 academically able children from modest-income families, over a third of whom went on to Oxford or Cambridge. This partly explains the steady increase in the proportion of Oxford undergraduates from private schools throughout the 1980s and 1990s; we estimate that up to a quarter of Oxford entrants in this period came via the Assisted Places Scheme. And the fact that they gained places with fewer A-level points, on average, than entrants from state schools illustrates the persistence of the “private school advantage” in admissions.

Labelling students as “state-educated” or “privately educated” still doesn’t tell the full story, and further analysis of the socio-economic backgrounds of Oxbridge undergraduates will help. But, for all that, recent progress in levelling the playing field is undeniable, and raises the question of whether the debate about the fairness of Oxbridge admissions has finally been settled. The profile of Oxbridge students is now much closer to that of UK sixth forms than it once was. Two-thirds of sixth-formers who gain top A-level grades are from state schools: the proportion of state-educated entrants to Cambridge has already surpassed that figure, and Oxford isn’t far behind.

Yet questions remain. Given that girls continue to outperform boys at A level, should the proportion of women at Oxford be far higher than 53 per cent? What implicit bias might still be at play in the admissions process, especially with regard to ethnicity? And, perhaps most importantly, why is there so little scrutiny of the social backgrounds of the majority of students now admitted to Oxbridge: postgraduates?

Claire Hann is an equality and diversity officer and researcher in the School of Geography and the Environment and Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder professor of geography at the University of Oxford.

- Would you like to write for Times Higher Education? Click here for more information.