Even by the sometimes lurid standards of performance artists, Jon John was something of a boundary pusher.

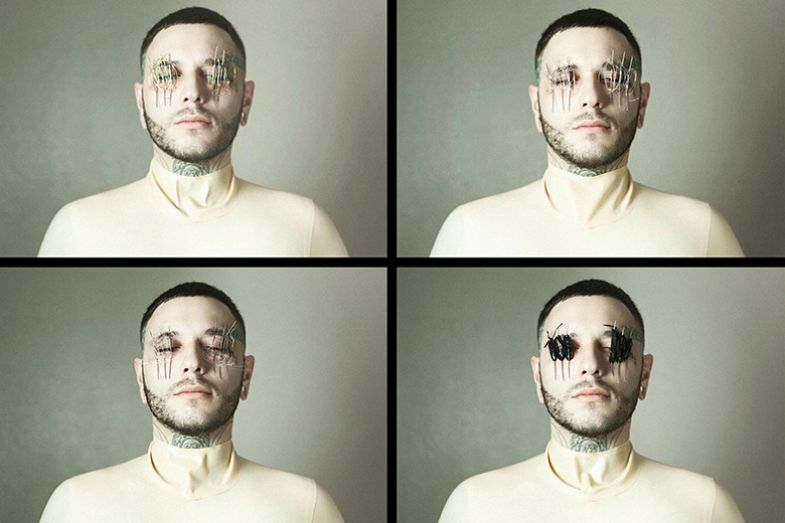

In one of his shows, known as The 2 of Us, the French-born artist, whose real name was Jonathan Arias, inserted an intravenous cannula into his arm, got down on his knees and repeatedly wrote those words in his own blood on a piece of fabric until he passed out. Since he was a body piercer (and ran a piercing and tattoo shop in East London), he created another show in which he inserted threaded needles above and below his eyes, resulting in dramatic flows of blood when he removed them on stage. The performance also featured a barefoot dance on rose thorns and a book bursting into flames.

Much of John’s artistic practice addressed issues of sickness and bodily decline. When he discovered a nasty-looking mole on his biceps, he made a gold cast of it and devised a performance called Gorgeous in which "body modification artist" Lukas Zpira cut it off on stage, while a third performer, known as Satomi, “gave birth” to the cast.

Shortly after he had established himself as a performer, John developed melanoma, which led to lymphoma and his death in 2017, at the age of 33. An installation piece called Roses Drinking Blood saw him put a white rose in a vase filled with his own “tainted” blood and produce a series of stop-motion images as the flower slowly soaked up the blood. After he had retreated to his mother’s house in south-west France, and just three weeks before his death, he live-streamed a goodbye performance called Love on Me, in which he burned tumour-shaped candles and wrapped himself up like an Egyptian mummy while friends came by to say their farewells.

Much of John’s work was obviously ephemeral and performed to small audiences. It would be regarded by many people as pointless, self-indulgent or even offensive. So how and why should a university engage with it?

Dominic Johnson, reader in performance and visual culture in the department of drama at Queen Mary University of London, researches and writes about some of the “more extreme” forms of performance art. “The exploration of pain, endurance and transformation”, he notes, has long been central to the genre – in this case enhanced by John’s extensive travels to witness initiation rituals involving ordeal, and his interest in “recuperating and reframing” these “ethnographic practices”.

No one who witnesses “an act of self-injury in an intimate supportive situation”, Johnson goes on, can “help caring for the person…I’m interested in art practices which seem to command a response. It’s difficult to feel blasé about them, even if you respond violently. That’s why I want to think about such work and teach it and show it.”

Johnson believes that it is often unclear, particularly in the case of “marginalised artistic practices”, whether the work will stand the test of time. He cites the case of a sculptor and performance artist called Stephen Cripps, who died in 1982 and had been largely forgotten, but was recently the subject of a major exhibition in Basel. When an artist dies young, he argues, “you need to hang on to the stuff and make it safe and accessible, so that at whatever point people want to look back on it they can. Universities have a lot of resources and space.”

Since Johnson plans to use John’s work in his teaching and research, he was able to persuade Queen Mary to acquire his archive – which is every bit as startling as his performances.

Source: Estate of Jon John/Queen Mary Archives

University libraries and archives own vast amounts of unusual material (as well as some genuine treasures). Examples in different UK institutions include a major collection of Soviet propaganda posters, extensive documentation relating to Welsh settlement in Patagonia and even marzipan busts of the politicians who launched the Social Democrat Party in 1981. At Queen Mary, according to archives officer Stephanie Rolt, some of the notable oddities include a botanical specimen book with pressed algae samples; an anonymous travel journal from the Middle East containing pressed flowers, papyrus and a parrot feather; and a chemistry professor’s papers, which happens to incorporate information about the 1964 revolution in Sudan.

In 2017, again at Johnson’s instigation, the university acquired the archive of another performance artist, Ian Hinchliffe (1942-2010). This, Johnson has written, contains “massive caches of photographs, flyers, posters, sketches for sets, scores and scripts, letters, agreements, and clippings. The range of his work is staggering, from one-off interventions in art centres and pub theatres, to film collaborations with [director] Mike Figgis, to a surprising commission to make a participatory event for children in South London in 1973 (Hinchliffe was physically ejected from the theatre by the children, and the police were called).” Queen Mary also decided to accept Hinchliffe’s beautifully detailed fishing diaries, although it turned down his fishing rods.

So university archives have more than their share of startling and bizarre material. Yet the John archive still stands out. Here we can find the blood-stained fabrics produced by performances of The 2 of Us, which formed part of a posthumous exhibition called The Perforated Body at the annual conference of the Association of Professional Piercers in Las Vegas in 2018. Other items include a ceremonial anklet and “cobra tongue” (a cheek-piercing spike with a chain hanging below), both brought back from Sri Lanka; the blood-stained homemade knife used in Gorgeous; mirrored eye patches and a pink wig that changes colour with the temperature. Not to mention a test tube of congealed blood, the original mole and its golden replica.

“It is rare even for archives of visceral performance to actually contain viscera,” Johnson comments. Looking at such material, he suggests, may perhaps bring us closer to the original experience of spectators at John’s shows than watching poor-quality videos on YouTube.

Source: Manuel Vason, Live Art Archives, University of Bristol Theatre Collection

One of the few parallels to John’s collection is the archive of the Italian performance artist Franko B, held at the University of Bristol as part of its theatre collection.

He was “top of the list” when the Tate galleries “wanted to engage with live art”, explains Julian Warren, keeper of digital and live arts archives at Bristol. For their first programme of such art in 2003, “they asked the Live Art Development Agency to commission a series of performances. Franko’s I Miss You was in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. A length of canvas was laid down the whole of it and he had two cannulas in his arms, and was naked and covered in white paint. It was set up like a catwalk runway and he walked from one end to the other and would bleed as he went, and he would get to the end, pause, stop and return. This went on for a few minutes with the audience either side of the runway.”

Franko B was keen for his archives to be preserved and so approached Bristol, which began receiving material in 2008. The various bloodstained objects the archives contain posed an unusual problem for the conservators, says Warren, because they “usually charge for cleaning the blood off. We said: ‘It’s absolutely not about cleaning the blood and white body paint off. These stains are meant to be kept.’”

Asked about the paradox of trying to preserve something as ephemeral as a one-off performance, Warren responds that the archivist’s task is “not about preserving the event but the documentation of the history. In that way, the Franko B archive is no different from many other kinds of archive. It’s the evidence that things happened in order that history can be researched...It’s preserving the process, like the records of how a company operated and developed.”

The archivists' initial fears that the material might fall foul of the obscenity laws proved to be unfounded, but it did raise practical and ethical issues around human remains. They consulted the curator of the university’s pathology museum at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, who passed them on to the Human Tissue Authority. In the event, the university was allowed to retain the fragments and fluids from John’s body but not to put them on public display, photograph them or scientifically test them without further consultation. Like everything else in the archives, explains Rolt, they are “stored in our environmentally controlled strongrooms”, to help preserve the material for as long as possible.

Source: Estate of Jon John/Queen Mary Archives

Despite the restrictions, Johnson is planning to build a series of public events around John’s archive, just as he already has around Hinchliffe’s. Future researchers and students will therefore get a chance to acquire a better sense of what the original performances were like, and to decide for themselves whether the work is inspiring, disturbing, mystifying, objectionable or just boring.

Yet this also raises a general question about the purpose of universities. It certainly makes sense for them to engage with cutting-edge and disturbing cultural phenomena. But they are also “respectable” institutions, in receipt of public money and rooted in local communities that often have more conservative values. Something that would attract no controversy in a pub theatre, never mind a conference of piercers, might be judged by rather different standards in a university setting. What would Johnson say to someone who objected to Queen Mary's storing material such as John’s?

“Keeping this archive is about keeping material for posterity which is at risk of loss or disappearance,” he replies. “Universities should be committed to intangible cultural heritage: things important for this culture or a subculture [but] which can’t yet be fully quantified as valuable.”

For him, the reputational risks involved are “really minimal”, given that archival material is generally hidden away. “I would be very wary of not keeping it for fear of some imaginary person who might not exist but who takes issue with something kept under lock and key in a refrigerated room where the stuff cannot be stumbled upon...Somebody would have to be on a very particular crusade to rid universities of all challenging material.”

后记

Print headline: Bodies of work