The marketisation of higher education has been accompanied by sharp increases in the use of counselling and occupational health services by UK university staff, according to a new study.

Responses to Freedom of Information requests by 59 institutions showed that counselling referrals climbed by an average of 77 per cent between 2009 and 2015, while occupational health referrals rose by 64 per cent.

The figures are detailed in a report published by the Higher Education Policy Institute on 23 May, Pressure Vessels: The Epidemic of Poor Mental Health among Higher Education Staff, written by Liz Morrish, a visiting fellow in the School of Languages and Linguistics at York St John University.

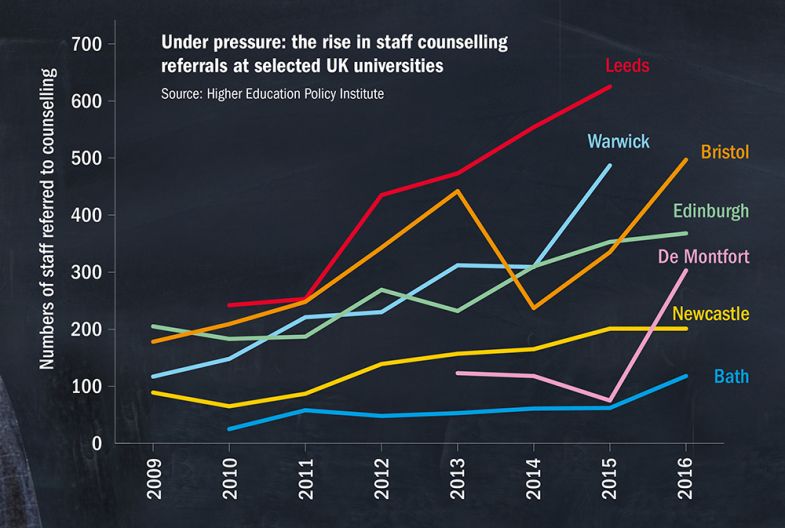

Some universities reported particularly large jumps in the number of referrals, with many of these coming after the rise in tuition fees in England in 2012, which is associated by many with increased pressure on staff to enhance the student experience. Between 2013 and 2016, for example, the number of staff referred to counselling services shot up by 146 per cent at De Montfort University and by 123 per cent at the University of Bath.

Some longer-term increases were even larger: for example, between 2009 and 2015, the number of referrals soared by 316 per cent at the University of Warwick, and by 126 per cent at Newcastle University; while between 2010 and 2015, the rise at the University of Leeds was 158 per cent.

Rise in staff counselling referrals at selected UK universities

In terms of occupational health, referrals at the University of Kent rocketed by 424 per cent between 2009 and 2015, and by 179 per cent at the University of Cambridge.

Women appear to be particularly at risk – 70 per cent of those referred for counselling and 60 per cent of those sent to occupational health were female – while professional services staff accounted for 65 per cent of occupational health referrals.

Dr Morrish’s report says that the catalysts for concern about mental health in universities included the suicide, in February 2018, of Malcolm Anderson, an accounting lecturer at Cardiff University. He fell to his death at Cardiff’s business school after struggling to cope with his mounting workload, an inquest heard.

Dr Morrish says that academic workloads are too high and that researchers suffer increased pressure because of the use of performance management, which has introduced expectations that academics should consistently publish research of a certain standard, or attract set levels of grant income, or face potential dismissal. This has been facilitated and driven by, Dr Morrish argues, the growing availability of metrics from national exercises such as the research excellence framework, and from university league tables.

Another concern for Dr Morrish is the expanding use of “precarious” fixed-term contracts by UK universities – 33 per cent of academics were employed this way in 2017-18 – which increase pressure on staff.

More broadly, she says, “a message from management that one is never doing enough” can “rapidly lead to employee burnout”, and that bullying and competition blight academics’ lives.

“Academics are inherently vulnerable to overwork and self-criticism, but the sources of stress have now multiplied to the point that many are at breaking point,” Dr Morrish said. “It is essential to take steps now to make universities more humane and rewarding workplaces which allow talented individuals to survive and thrive.”

Dr Morrish’s proposed solutions include not scheduling workload “up to the max” and improving recognition for academic citizenship activities, reducing reliance on metrics-based performance management, and providing more secure employment conditions.

Many of the universities named in the Hepi report said that growth in the number of staff accessing counselling and occupational health services correlated with expansion of these services and efforts to encourage employees to make use of them.

In the report’s foreword, Mike Thomas, vice-chancellor of the University of Central Lancashire, says that repeated studies indicate “a deteriorating level of sector confidence, frustration about its direction of travel and an increasing level of poor mental health”.

“[The] report clearly indicates, with evidence, that directive, performance management approaches are counter-productive to the output, efficiency and effectiveness of the organisation and also to staff well-being and mental health,” Professor Thomas writes. “If such an approach works, why are so many of our colleagues so unwell and continue to be so?”

Universities UK said that the mental health of staff and students was a “priority” for institutions. “Across the sector, there are many practical initiatives to support staff in mental health difficulties, to improve career paths and workplace cultures,” UUK said.

“Universities do recognise that there is more that can be done to create the supportive working environments in which both academic and professional staff thrive, including ongoing conversations about the structural conditions of work in higher education.”

后记

Print headline: Staff ‘at breaking point’ as counselling demand soars